The Dark Zone

If the axiom ‘how you do anything is how you do everything’ is true, then it isn’t a surprise to note how modernity’s love of reductionism has its fingerprints all over the movement world.

All too often I see people training in a compartmentalised way, working parts of their body in one plane of motion, seemingly forgetting that movement takes place in glorious 3-D - Sagittal, Transverse and Frontal (see Terminology below for a description of what these are).

A powerful example of self-limiting movement is to keep the knee over the toe - flexing the knee without internally or externally rotating it and, in the case of weightlifting, only squatting a certain depth, thus artificially restricting the range of movement. The knee over toe belief originates from a 1978 Duke University which demonstrated an increase in shearing force at the knee joint when participants knees were allowed to travel past their toes when squatting. A 2003 Memphis University study confirmed this - yet also found that hip stress increased nearly 1,000% when forward movement of the knee was restricted.

In Anatomy in Motion, Gary Ward touches upon the concept of the dark zone, which means movement we’ve forgotten we can access. For many of us, taking the knee past the toe is considered risky because it’s a place we haven’t been in a long time and have been conditioned to believe it is unsafe and may cause injuries. Neuroplasticity has shown how the brain has the ability to change and adapt as a result of experiences, and neural pathways change in response to how we move, so by restricting movement we essentially ‘forget’ these are safe, healthy places we can be.

An example of this is a 2006 study in which participants four fingers were taped together for five hours; sensors that measured brain activity before and after the taping showed that cortical reorganisation is extremely rapid in adapting to altered sensory input. In short, after only 5 hours the brain began the process of reorganising itself to reflect these changes and treat the four fingers as one.

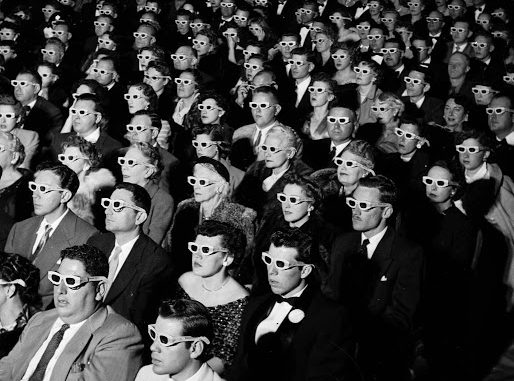

This was illustrated in a more extreme way by amputating a monkey’s finger which showed how the neurons no longer receiving signals from the missing finger had been appropriated by the networks responding to signals from the other functioning nerves. Similarly barbaric experiments on kittens (sewing newborn kittens single eye shut for the first month of life) and monkeys (rearing newborns in complete darkness for the first three months of life) showed how critical environmental input is to normal, healthy development.

(We’ll explore the question of science and morality another day, but it’s a point I feel is worth touching upon after reading about the numerous ways ‘experimental’ animals are treated in the name of science and progress.)

This may all seem as if I’ve gone off on a tangent, yet by consistently not experiencing the full range of our movement we create a comfort zone. This is fine until one day the unexpected happens and we trip, fall or roll our ankle and enter the dark zone of unfamiliar movement. It’s no wonder we act accordingly – panic and protect!

By understanding that the brain is pliable and adjusts to what we do in our lives, we can reintegrate forgotten movement back at any age. It’s true, children learn things at a much quicker rate than adults, but that doesn’t mean we can’t challenge ourselves. I know someone who learned to tumble at 42, despite initially not even being able to do a forward roll. If we choose to move into spaces that feel unfamiliar we challenge our system to react to being in that space and if we don’t use it there’s a good chance we’ll lose it.

For those of you wanting guidance on this path, Billy offers in-person and remote Natural Movement sessions.

Alternatively, if you are looking to incorporate this in a more controlled place because you have pain or restricted movement, I look forward to connecting over a session.

- F

TERMINOLOGY

CONCENTRIC: The concentric phase is when we are doing an exercise and the muscles we are targeting are contracting and the muscle fibres are shortening. Bringing the hands up in a bicep curl is the concentric phase.

ECCENTRIC: An eccentric contraction is the motion of an active muscle while it is lengthening under load. When you’re slowly lowering a weight under control back to the starting position, that’s the eccentric phase.

FRONTAL PLANE: The body as viewed divided into front and back halves.

ISOMETRIC: There is no movement at a joint and the muscle fibres remain the same length. If you are doing a bicep curl and stop to hold it in a position it becomes an isometric exercise. It’s also known as static strength training.

NEUROPLASTICITY: The capacity of neurons and neural networks in the brain to change their connections and behaviour in response to new information, sensory stimulation, development, damage, or dysfunction. Rapid change or reorganization of the brain’s cellular or neural networks can take place in many different forms and under many different circumstances.

SAGITTAL PLANE: The body as viewed divided into left and right halves.

TRANSVERSE PLANE: The body as viewed looking from above or below.

What are the most common misconceptions about furniture free? Well these are my top three!