Health

A reductionist approach to health is symptomatic of an old paradigm, one that is being undermined more and more by research showing that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

I’ve often wondered why it seems, as a culture, so many of us are unhealthy, unhappy and sick. I never really believed it was the baseline human experience and, as I dug into this, it became clear that what constitutes health and how we can cultivate it, requires a radical rethink of how we live our lives. Health isn’t just the absence of disease or infirmity, but a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being - defined as such by the World Health Organisation.

Despite vast sums of money being spent every year (in 2015/16 , the overall NHS budget was around £116.4 billion) people are continue to be ill and struggle to deal with long term chronic issues. The proportion of patients being prescribed opioid painkillers by their GP has doubled in 15 years and, in 2017, there were nearly 24 million opioids prescribed.

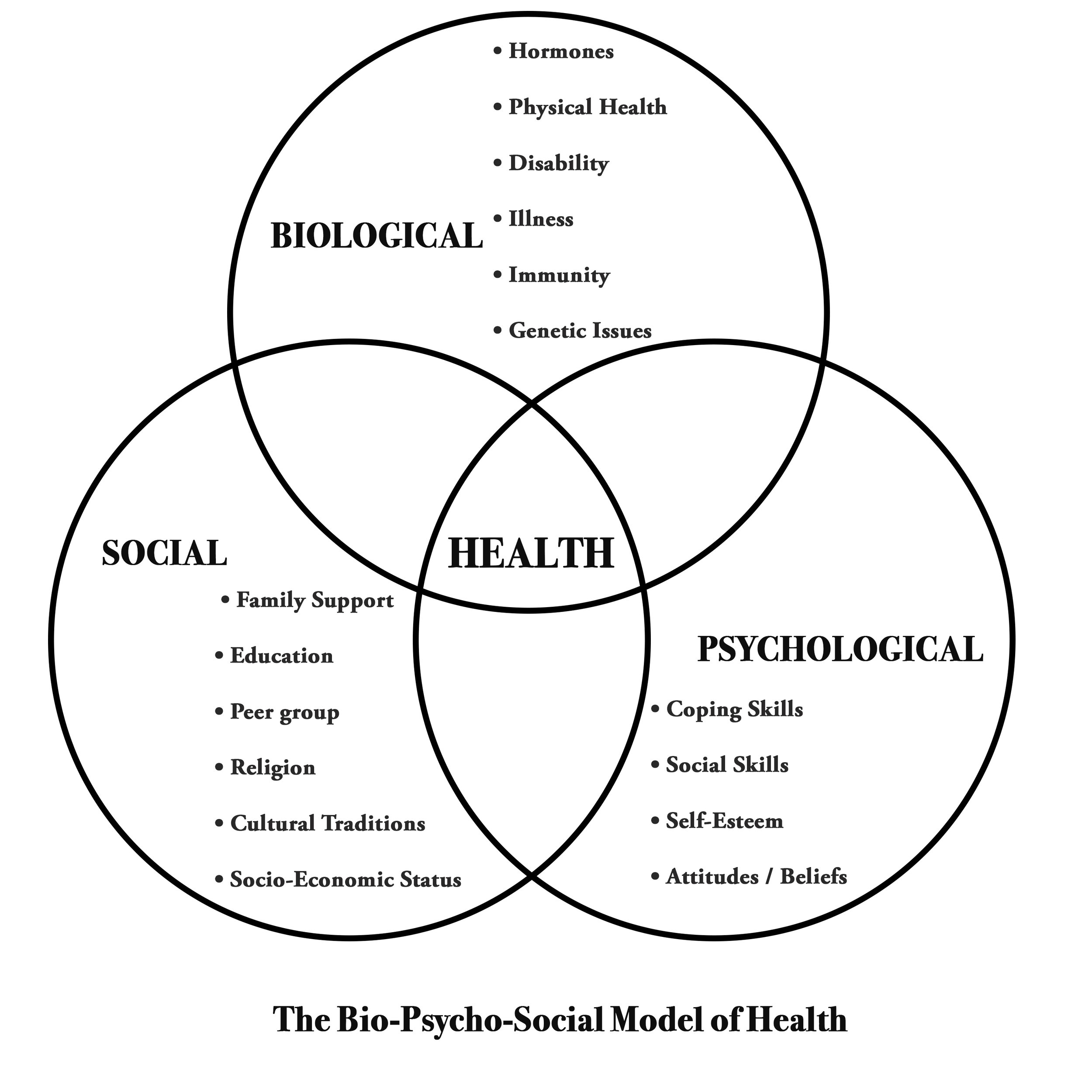

Last week I came across the Biopsychosocial model of health which affirmed my approach and the way I approach my sessions with clients:

The Biopsychosocial Model of health and illness as proposed by Engel (1977) implies that behaviours, thoughts and feelings may influence a physical state. He disputed the long-held assumption that only the biological factors of health and disease are worthy of study and practice. He argued that psychological and social factors influence biological functioning and play a role in health and illness also. This is a more realistic model in light of the role lifestyles play in a society having entered the new millennium. This new theoretical model therefore has been developed in an attempt to improve on the disease approach and narrow view with respect to health and illness held by the medical model so that psychological and social factors of the individual can also be considered.

(Source)

There is certainly a place for the biomedical model; the marvels of modern surgery attest to that.

But there is also a lot of wiggle room for a more nuanced approach to health and one that seeks to treat the individual; people may have exactly the same symptoms but that doesn’t mean the approach to curing them will be the same.

Research has shown that taking an active approach to managing pain results in improved quality of life, increased function and decreased pain. When professionals are seen as authorities who prescribe things that’ll fix us, we need to question ourselves and ask how much of our power we’ve given away. Are we blindly following these people? Being prescriptive is ‘making or giving directions, rules, or injunctions as well as sanctioned by long-standing usage or custom’. Just because we’re prescribed something that conventional medicine determines will fix us, doesn’t mean it will and can lead to a loss of personal accountability and responsibility for our lives. Every day we make small choices that contribute to our health or the deterioration of it - that morning cake in the office, taking on extra work and resenting it, ignoring niggles and hoping they’ll magically disappear. If we reframe our relationship with the professionals who treat us and become an active participant in keeping healthy we can reduce the likelihood of dependency on these people and return visits to them.

Every Pain & Injury clinic session is different because every body I see is different; they are the sum total of all the events that have shaped them. We all share the same physiology, but we express illness and mal-adpation in different ways. Sometimes pain is an echo of former times, a living relic of our past that’s embedded itself into us, a mechanism that over time has grown faulty as it wants to keep us safe.

For those ready to do the work, I look forward to connecting over a session.

- F

DO WE ACTUALLY EXPERIENCE PAIN, OR IS IT MERELY ILLUSION?

What are the most common misconceptions about furniture free? Well these are my top three!