Sole Rebel : The Problem With Orthotics

READ

‘Should I get rid of my insoles?’ is a common question I get asked and, to save you the trouble of reading this, my answer is, ‘it depends’. Not very helpful, I know, I prefer to encourage clients think critically and make their own informed decisions. In a culture where we’ve been brought up to defer to authority it can be hard to form our own opinions and stick to them. Yet being an authority doesn’t automatically equate to being knowledgeable; just because someone has studied something doesn’t mean they’re up to date with current information.

Appeal To Authority

Insisting that a claim is true simply because a valid authority or expert on the issue said it was true, without any other supporting evidence offered.

In this age of information saturation, I find it useful to have a few questions I use as starting points:

‘What’s the intention of ______?’

Getting a grasp of the logic and theory behind the reason for doing something can help you decide if it makes sense or not.

‘Who benefits from this?’

It’s important to understand that some people have a vested interest in selling us things and it’s easy to be convinced by slick advertising, PR or a huge Instagram following.

‘What would our ancestors have done?’

This one is pretty hard to answer conclusively, but it’s more about stepping outside of the current culture and looking at the bigger picture. If we survived hundreds of thousands of years without insoles, did anything change that caused us to want or need them? A lot of problems stem from the environment we’re living in and not physiological flaws we’re born with.

What’s the intention of an arch support if it weakens the arch?

The foot is designed to move from a mobile adapter to a rigid lever via pronation and supination and uses 26 bones, 33 joints, and over 100 tendons and muscles to accomplish this. When walking, the closed chain environment ensures there is only a fixed amount of movement available and if insoles limit or restrict movement then the body will ‘borrow’ movement from elsewhere.

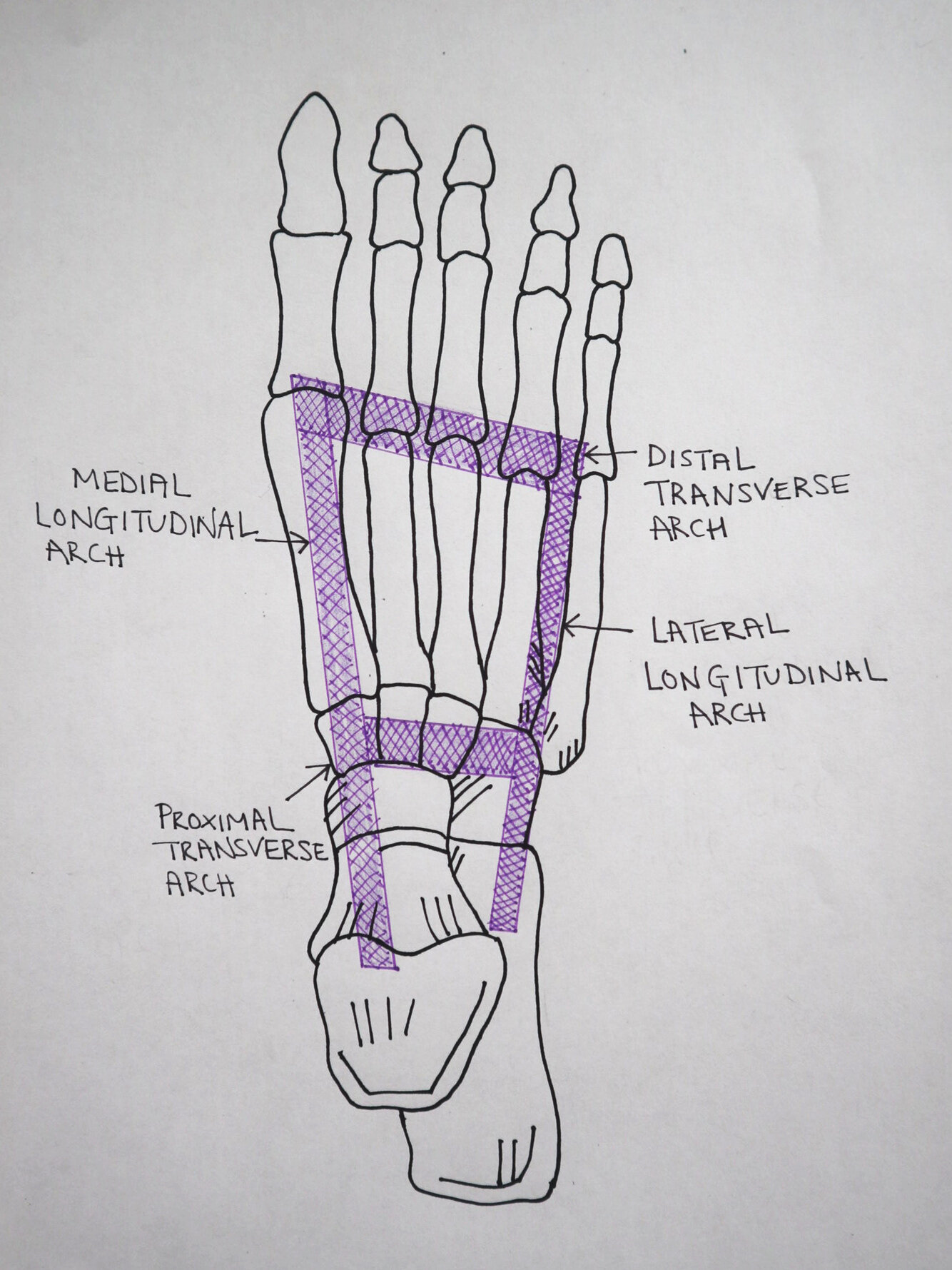

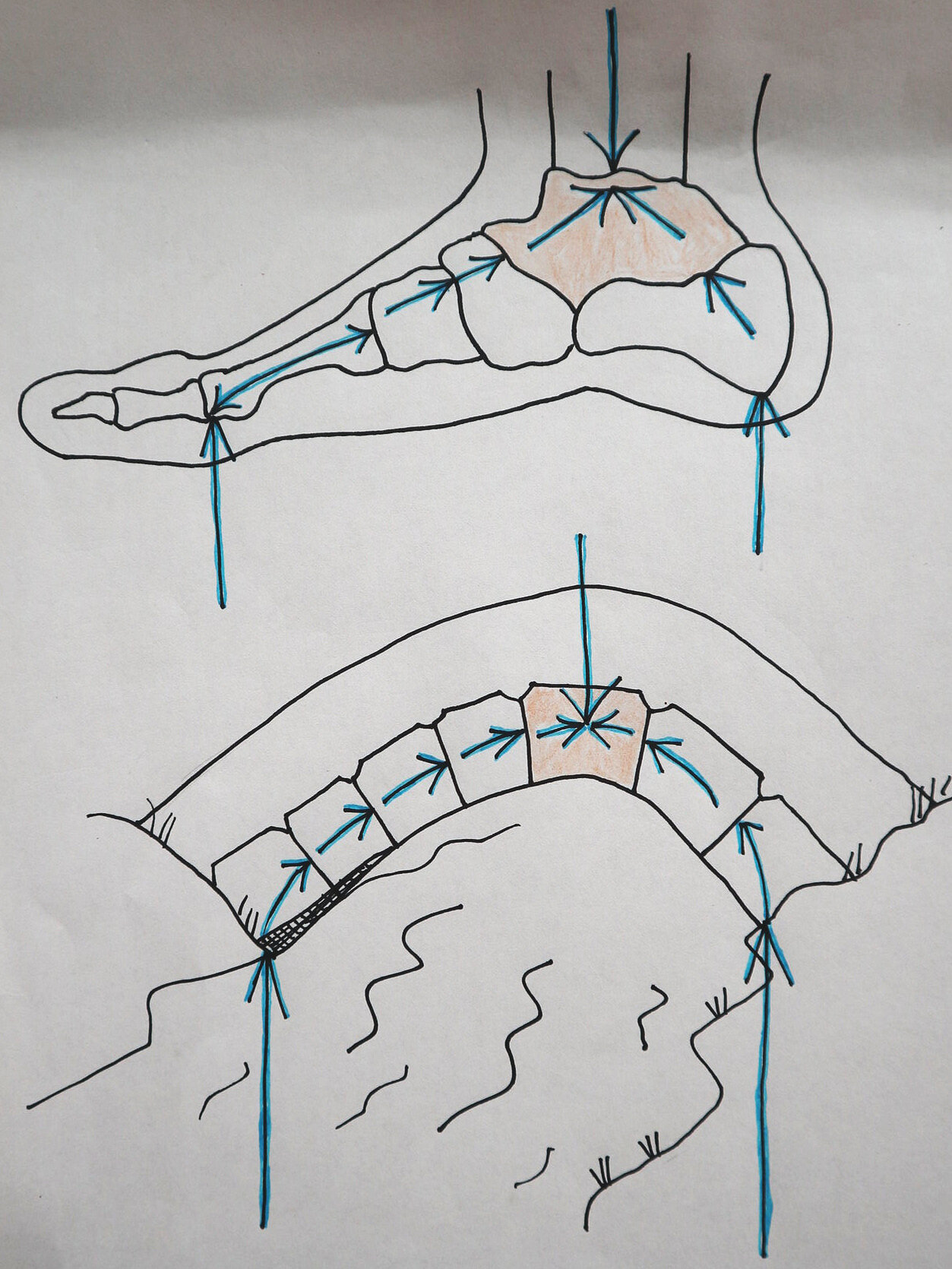

Within the foot there are three arches which support our entire structure, with the weight coming down through the ankle (talocrural joint). An arch is considered one of the strongest geometric shapes because it distributes force evenly along its curvature and its strength comes from the weight from above being carried outwards along the curve of the arches; the more weight pushing down from the top of the arch, the stronger it gets as it just pushes the pieces of the arch together harder.

Because of the amount of weight that the foot is expected to bear, arch support removes the body’s ability to successfully manage its own mass and this can end up having a host of unintended consequences including muscle atrophy, a reduction in ankle mobility, heel pain and achilles tendon pain. Weakness rarely corrects itself through further padding, cushioning and protection because if you artificially support the body, the body will stop supporting itself. Just like the old maxim says, ‘use it or lose it’.

If we think about the concept of an arch support, we realise that it doesn’t make logical sense because if an arch is weakened with forces pushing up instead of pushing down, then arch support serves to weaken the structure not strengthen it. Is it too far of a leap to consider that the term arch support could be considered as doublespeak?

Doublespeak

Misleading or false language used to make a negative situation sound better or that can be understood in more than one way that is used to trick or deceive people

Words that say one thing yet mean something completely different; language which pretends to communicate but doesn’t.

Orthotics

Now, I’m not going to throw the baby out with the bath water, because you may have done your research, visited specialists and decided that orthotics are for you. When choosing which orthotics to use, it’s best to go to a professional who will utilise a variety of methods to design your insoles such as pressure plates, video, 3D scans and biomechanical assessments of how you stand, walk and run. The more information gathered, the more likely it is that your insoles will be precisely designed to adapt to your needs.

Bear in mind:

They are used as a part of a treatment plan and are not used in isolation as a treatment in and of themselves.

They are designed and manufactured to fit you individually.

They are made from a suitably ridged material to allow them to resist the pathomechanical forces being generated.

The person prescribing them has relevant credentials - they’re not just sales people.

When to use orthotics:

Post-surgery for tears, tendon dysfunction. This is normally a temporary orthotic, to provide ‘rest’ to tissue, facilitating healing and repair.

Structural related issues - e.g clubfoot, coalitions or scoliosis.

Accommodative orthotics designed as pressure redistribution for foot ulcers, severe foot deformities or amputation sites.

Check for:

Worn treads and for signs of wear and tear.

Cushioning and padding - take note of whether this has changed over time.

Return of original problems - a sign the orthotics may no longer be working as intended.

Excessive moisture and bad smells.

A correct fit. They don’t slide around in the shoe.

Conclusion: We weren’t born with insoles

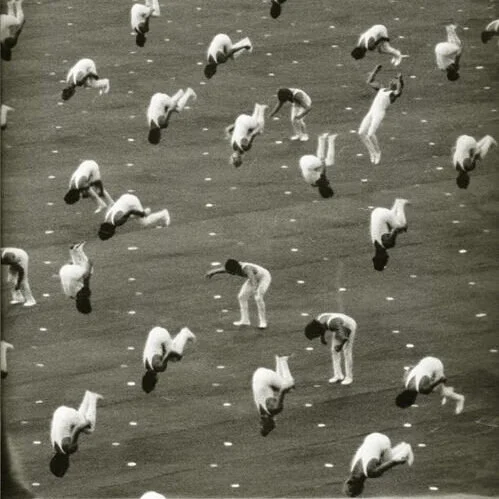

Because most of us have worn shoes all our lives and rarely spend much time walking on uneven or challenging terrain, we’ve created a perfect storm resulting in foot problems such as compromised arches and is why so many of us opt for arch support and insoles. Rigid or overly cushioned modern footwear weakens the structural integrity of the foot as well as the muscles and tendons in the lower leg and yet for most of human history we’ve survived by being barefoot or wearing shoes that are very thin which raises the question as to whether it could be the footwear that is part of the problem and not the solution.

Orthotics can act as a kind of crutch or distraction from the deeper reasons as to why we’ve ended up with dysfunction to begin with. They require very little lifestyle change on our part and we don’t have to take an uncomfortable look at whether we’ve been complicit in the creation of our problems.

Yet I’m not suggesting you hack out your insoles and defiantly burn them; somewhere there is moderation and balance. To undo an entire lifetime spent in thick-soled shoes that restrict or alter movement has created tissue adaption that takes time to undo and isn’t a transition that will happen overnight. Radical change rarely gives long-term positive results. Instead, make small changes that you consistently stick to, for instance spending 5 minutes a day barefoot or making your own cobblestone tray.

So, in summary, the best way to answer whether you need insoles or not is to educate yourself and listen to what your body is telling you - if your insoles are uncomfortable or the pain hasn’t gone away then take them out and notice what happens.

- F

WATCH

REFERENCES:

Cavanagh, P.R., Pollock, M.J. and Landa, J. (1977) A biomechanical comparison of elite and good distance runners. Annals New York Academia Science, 301, 328-345.

Curtis CK, Laudner KG, McLoda TA, et al. The role of shoe design in ankle sprain rates among collegiate basketball players. J Athl Train 2008;43:230–3

Goss DL, Gross MT. Relationships among self-reported shoe type, footstrike pattern, and injury incidence. US Army Med Dep J 2012;Oct-Dec:25–30

Jarvis HL, Nester CJ, Bowden PD, Jones RK. Challenging the foundations of the clinical model of foot function: further evidence that the Root model assessments failed to appropriately classify foot function. J Foot Ankle Res 2017;10:7.

Kulmala, J-P., Kosonen, J., Nurminen, J., & Avela, J. (2018). Running in highly cushioned shoes increases leg stiffness and amplifies impact loading. Scientific Reports, 8, [17496].

Kirby KA, Spooner SK, Scherer PR, Schuberth JM: Foot Orthoses. Foot & Ankle Specialist 5: 334, 2012.

McPoil TG, Hunt GC: Evaluation and management of foot and ankle disorders: present problems and future directions. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy 21: 381, 1995.

Nester CJ: Lessons from dynamic cadaver and invasive bone pin studies: do we know how the foot really moves during gait? Journal of Foot and Ankle Research 2: 18, 2009.

Ryan M, Elashi M, Newsham-West R, et al. Examining injury risk and pain perception in runners using minimalist footwear. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:1257–62.

Theisen D, Malisoux L, Genin J, et al. Influence of midsole hardness of standard cushioned shoes on running-related injury risk. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:371–6.

Williams DS, McClay I, Baitch SP: Effect of inverted orthoses on lower-extremity mechanics in runners. Medicine and Science in Sport and Exercise 35: 2060, 2003.

It’s important to recognise that we are far from complete in our knowledge and we know very little about the way about how the body actually works - that’s why I really like reading these studies because they run counter to ‘accepted wisdom’ and challenge our prevailing norms.