Our Bones Tell The Story | The Screw-Home Mechanism

The surface of our joints tells the story of how they are designed to move and the potential movement that’s available to us. We know that our knee bends and straightens, but often forget it also has the ability to rotate. Rotation does in fact occur at the knee, and is greatly affected by both our feet and our hips; as the knee straightens (extends), the hip and knee are both externally rotating but the hip rotates faster which creates a relative internal rotation at the knee.

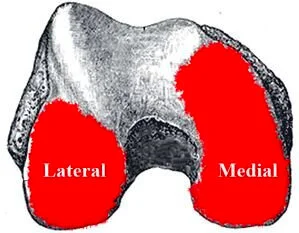

A view of the distal end of the femur showing the unequal amount of joint surface available for movement internally and externally.

The femur has two rounded ends (condyles) and one side has more surface area than the other, allowing more movement internally (medially) than externally (laterally). After the lateral condyle has moved to full range there is still surface area for the medial condyle to move into and this is the known as the ‘screw-home’ mechanism.

The ‘screw-home’ mechanism is the rotation between the tibia and femur and is considered to be a key element to knee stability for standing upright. This mechanism serves as a critical function of the knee and it only occurs at the end of knee extension, between full extension (0°) and 20° degrees of knee flexion.

As the knee approaches terminal extension it is in its most stable position; the tibia is in the position of maximal stability with respect to the femur and the leg is able to support the body weight despite the quads not being activated. The anterior cruciate ligaments (ACL) plays an important role in the process and any ACL problems may restrict or stop the screw-home mechanism.

Credit: Dr. Bhupendra Gosai

The screw-home mechanism reverses during knee flexion and when the knee begins to flex from a position of full extension, the hip internally rotates faster than the knee, this creates a relative external rotation at the knee.

Our symptoms may be at the knee, but we need to retrace the origins of dysfunction and improve mobility and joint-Loading capacity elsewhere

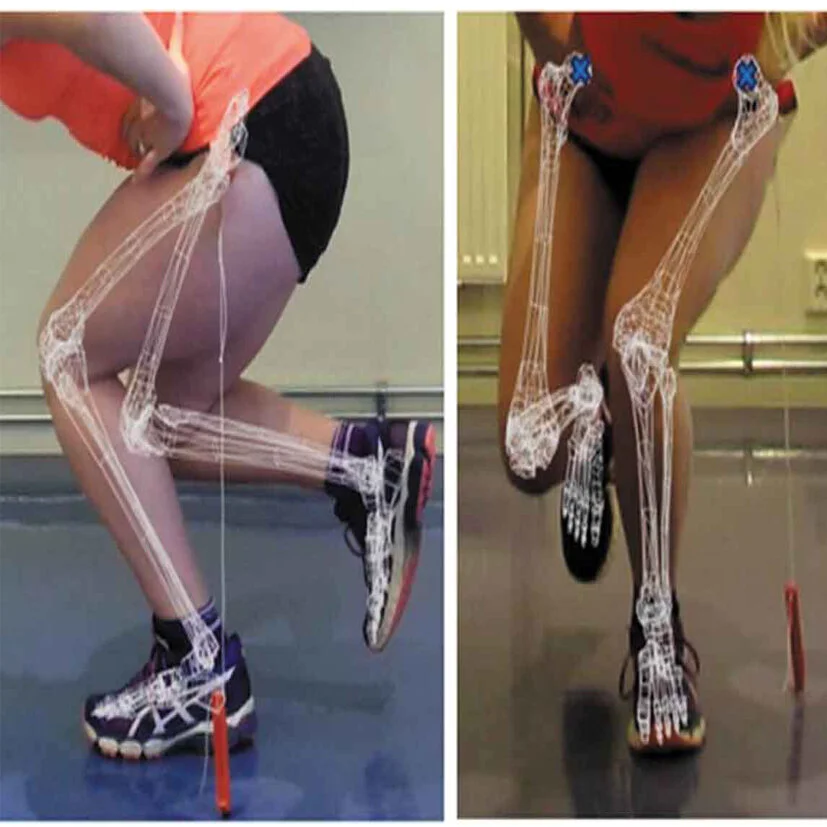

A supinated foot couples with an internally rotating hip and externally rotating tibia and the opposite occrurs in a pronated foot; an externally rotating hip couples with an internally rotating tibia. If any of these joint motions are not fully accessible or sequenced, it could potentially lead to excessive motion at the other joints, increasing mechanical stress and creating compensations and adaptions that lead to problems.

There are numerous potential ways in which any one person can compensate around dysfunction. Josh Landis describes two scenarios which can show up as knee pain:

An immobile navicular bone in the foot is preventing full pronation in the foot. A lack of adequate pronation then leads to increased subtalar inversion, which shifts the talus position medially. The talus shifting medially then neurologically inhibits all the muscles in the lower extremity moving laterally. Decreased muscle strength of the glute medius, TFL, and other abductors then destabilizes the hip leading to an aggressive knee valgus, and the medial knee becomes painful.

An unstable SI joint stuck in anterior torsion. This decreases the hip joint’s available external rotation. A lack of hip external rotation then becomes compensated for by increased external rotation of the tibia. Excessive external rotation of the tibia then leads to an imbalance between the lateral and medial hamstrings over time. The lateral hamstrings have more mechanical stress on them, and over time we start to get pain in the posterior lateral knee.

if the knee cannot fully extend the screw-Home mechanism can’t happen

In order to fully understand and resolve our knee symptoms, we need to consider rotational stability as well as take into account how things are functioning above and below at the hip and foot. Once we have this information, then it’s possible to integrate and couple movements at the foot, knee and hip. If you’re unable to fully straighten your legs then your quadriceps are always activated and this means that your body has to rely on muscles and ligaments for support and stability, leading to over-work, pain and increased risk of injury.

- F

REFERENCES

Hallén, L. & Lindahl, O (2009). The “Screw-Home” Movement in the Knee-Joint. Acta Orthopaedica. 37. 10.3109/17453676608989407

Laubenthal KN. A quantitative analysis of knee motion during activities of daily living. Phys Ther 52(1):34-43;1972

Rowe PJ et al. Knee joint kinematics in gait and other functional activities measured using flexible electrogoniometry: how much knee motion is sufficient for normal daily life? Gait and Posture 12:143-155;2000

There seems to be a complete terror of peeling back the layers to examine the root causes of issues as well as an accompanying terror that, once examined, the best solution would be a simple one.

Let these experts stand up and be judged by the outcomes of their policies and not just by the amount of papers they publish.

Is climbing a wall the most important movement skill of all? Yes! Maybe. In this video I'll discuss why I think the wall climb is such a useful skill to have.

Trees are boring, so I decided to un-boring them with some clambering and a hand made Christmas tree topper.

Humans, like all creatures of this World, are regulated less by our temperament and more by our environment which constrains and keeps us in check.

This environment has changed considerably thanks, in part, to central heating.

Like the Amish, we must now be intentional with how we design our lives and recognise there is a cost to all new things, a cost that may not be known for decades.

I've lived the last 7 years of my life without furniture. Is it comfortable? Is it good for you? And do people thing you are weird? Yes, but you should probably watch the video for more information.

Athletes are the pinnacle of health and fitness in our modern age. Or are they?

Well...... It's Complicated

Are you normal? Well that just might not be that good for you, lets take a look at how the normalization of the modern world is damaging our health and even our ability to understand the world around us.

I've stopped drinking as much caffeine, except for when I drink more. I've been experimenting and wanted to share my decaffeinated experience.

I've always had a bit of a problem with ergonomics, while some of the ideas put forward by it seem logical on the surface, the unfortunate truth is that even the people that stringently follow the principles of ergonomics end up just as ill and injured as the people that don't.

It’s always satisfying when you come across a term or phrase which encapsulates something in a way that's surprising and yet makes total sense. In modern times, it also helps that concepts are only as long as a Twitter post; the shorter and more succinct the better so our over-stimulated attention spans can grasp it.

Where I somehow manage to link obesity with the end of the British Empire.

It’s important to recognise that we are far from complete in our knowledge and we know very little about the way about how the body actually works - that’s why I really like reading these studies because they run counter to ‘accepted wisdom’ and challenge our prevailing norms.

Unless sedentary habits change, this generation of children could end up with hip fractures in their 40s and 50s instead of their 70s.

Falls in the 40-plus age group have increased 20% from the previous generation, so it seems likely this figure will only increase for the coming generation who’ve spent the majority of their childhood sedentary and with low bone density.

A deep dive into safetyism, its origins and what it means to live in a highly unnatural ‘safety-first’ culture.

Head-loading is impossible to perform correctly without achieving an ideal head and neck alignment. Alongside the development of the relevant stabilising muscles that develop, so too does a particular gait pattern which is a third more efficient than our normal walking gait.

Ideal posture is the position from which the musculoskeletal system functions most efficiently and there is a direct relationship between chronic poor posture and chronic pain.

Wellness banking the newest idea to encourage people to spend responsibly all the while improving their physical health. To benefit from wellness banking you must share more personal data with your bank than ever before and allow it to track your movement, exercise routine and diet; the more you’re willing to share, the more rewards you’ll receive.

‘The healthier you get, the more we’re able to offer you. It’s a virtuous circle that’s good for you, good for us, and good for society.’

Tend your inner fire this March by joining Billy at this free online summit.

You’ll learn about natural movement and how to embody your natural masculine (if you don’t do this already).

I cannot guarantee you will leave the summit a better person, but you might.

Modern life has come to resemble that of the adult sea squirt; thinking is prioritised, movement is downgraded and human experience can be experienced entirely though a screen. In this year-long experiment of inactivity and inertia (cheerily marketed as ‘lockdown’), will we pay the price for neglecting a fundamental part of our nature?

The Royal Society for Public Health has called for the introduction of ‘activity equivalent’ calorie labelling and have suggested packaging containing information on how much physical activity it takes to burn off the calories. Many of the public health interventions are focused on the individual taking full responsibility for their health, however it must be noted that the environment around us has a huge impact on the decisions we make.

Healthwashing harnesses dubious claims such as ‘natural’ or ‘clean’ and turns them into extremely powerful marketing terms, selling you a lifestyle or a vision of who you could be if you bought their products. The words chosen are deliberately misleading and even meaningless, used because they are unregulated - it’s worth remembering that the front of a product’s packaging is pure marketing only.

Never have we had so much data and information about our health. Our wearable devices tell us all kinds of information about ourselves we could only dream of knowing in the pre-smartphone stone age. We measure our heart rate and track our steps - but does any of this information translate to changing our behaviour?

Falls aren’t something that ‘just happen’ because you’re getting older and they’re not ‘inevitable’; they are preventable. With the fall rate in the 40-plus age group up by as much as 20% on the previous generation, researchers speculate it could be due to our increasingly sedentary lifestyles making us less steady on our feet and poor nutrition throughout our life.

Can we stay as sharp as a pin mentally if we never go outside, move around and keep our body in good shape? Likewise, if we focus entirely on what we look like, to the detriment of cultivating our mind, are we in balance? Movement is a key factor to maintain both the mind and body in a healthy state.

There are various stages of learning we go through in order to acquire new skills - we all start at the very beginning and over time, develop the skills and techniques needed. This model is a guide through the learning process, highlighting why obstacles exist and what the best ways to overcome challenges are each stage of the way.

Walking involves smooth advancement of the body through space with the least mechanical and physiological energy expenditure. If any part of the system is compromised then the body will rely on increasing energy costs to manage this.

I am delusional and gripped by mass hysteria.

This is a sentence no-one is likely to think about themselves; madness resides in others and not ourselves. As humans we have a terrifying capacity to justify ourselves and dig in deeper when our beliefs are questioned.

What are the factors behind this that compel us to follow others and are there consequences to our health if we stand out from the crowd?

We have grown to expect medicalised solutions to ageing be they through pills, surgery or new scientific breakthroughs which promise to confer health, longevity or even eliminate death altogether. Aubrey de Grey, cofounder of the SENS Research Foundation, proclaims the first human being to live to the age of 1,000 has already been born. If ageing is seen as a disease, it reframes it into a treatable condition, facilitating therapeutic interventions and preventative strategies.

We’ve come to use ‘exercise’ and ‘physical activity’ interchangeably but they aren't the same thing and, if you read the small print whenever the Government or the NHS is imploring you to get fit, rarely do they mention exercise alone; they often say you need more physical activity. This distinction is really important to grasp; the guidelines aren’t prescribing exercise; they’re saying you need to move your body more.

What are the most common misconceptions about furniture free? Well these are my top three!