We’re All Sea Squirts Now

A sea squirt may look like a swaying tube, but looks can be deceiving; it is one of the most highly evolved marine invertebrates. They are members of the phylum chordata, which includes animals with spinal cords like fish, birds, reptiles, and humans, and their deceptively simply tubular adult body houses systems for digestion, reproduction, and circulation as well as a nervous system.

There are more than 3,000 known Sea Squirt species which can can survive up to 30 years in the wild and they are hermaphrodites - with both male and female reproductive organs. Sea squirt undergoes retrogressive metamorphosis, which means that very complex anatomy of larva transforms into very simple anatomy of adult animal. They spawn by releasing eggs and sperm into the water at the same time. After about three days, eggs develop into tadpole-like larvae, and they spread into the ocean by wiggling and twitching. The larvae uses a spinal cord connected to a simple eye and tail for swimming and a primitive brain helps it locomote through the water - but this doesn’t last long. Because the larvae aren’t capable of feeding, this free-swimming stage lasts only a short amount of time and, once it finds a suitable place to attach itself, a rock, substrate or some other solid object such as the hull of a boat, it never moves again.

Now it’s settled, the sea squirt starts the digestion of its own body and begins to absorb all the tadpole parts of itself - the tail, primitive eye, cerebral ganglion (brain-like organ) and notochord (spine-like structure). This process usually lasts 36 hours and leads to creation of sac-like creature equipped with two siphons and circulatory, digestive, and reproductive systems. Unlike other members of the chordate family which keep their spinal cords and brains for the rest of their lives, the neurons that control locomotion will never be needed anymore so it literally eats its own brain.

Retrogressive Metamorphosis

The complex anatomy of larva transforms into very simple anatomy of adult animal.

It is given this name because a progressive, active and alert larva metamorphoses into a retrograde and sedentary adult.

Embodied Cognition

For many centuries we have operated from the theory that our consciousness resides in the brain, snugly encased in our skull, separate and disembodied from the body it controls. The brain as control centre, shapes raw sensory data into an approximation of external reality and is summed up by Descartes famous phrase, ‘I think, therefore I am’. Could it be that our cognition is a product of how our we’ve evolved with our environment? Embodied cognition is challenging this long-held idea and posits that the mind is not only connected to the body but that the body influences the mind and may also be shaped by the world around us, ‘I am, therefore I think’.

Embodied cognition is the claim that the brain, while important, is not the only resource we have available to us to generate behaviour. Instead, the form of our behaviour emerges from the real-time interaction between a nervous system in a body with particular capabilities and an environment that offers opportunities for behaviour and information about those opportunities. The reason this is quite a radical claim is that it changes the job description for the brain; instead of having to represent knowledge about the world and using that knowledge to simply output commands, the brain is now a part of a broader system that critically involves perception and action as well.

Jeff Thompson, Ph.D

More research is needed into these claims but, if the body, brain, and environment interact through perception and action to give rise to intelligent behaviour, it would change the landscape of healthcare interventions and treatments. Perhaps the idea that the brain, body and the world are separate will be seen as archaic, replaced by a more holistic view of cognition and intelligence taking place simultaneously in the brain, the body and the environment around us.

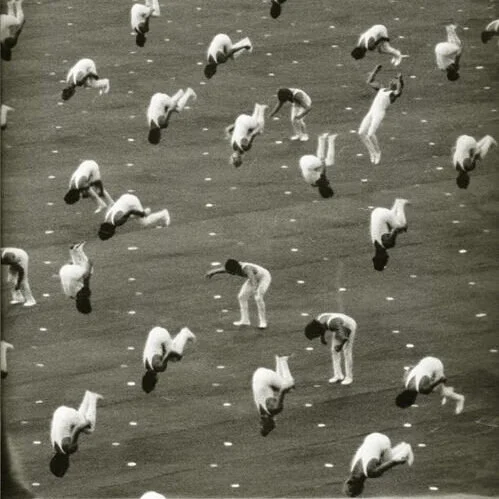

Our bodies are an important part of the learning process

As humans, we directly interact with physical stimuli through our five senses - touch, taste, hearing, smell and sight - to understand and navigate the world; we are all, literally, born to move. Movement stimulates the growth of new neurons and synaptic connections and increases the levels of endorphins, dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin, all of which play a role in how we deal with stress, our willpower and motivation, as well as regulating our emotional state.

Many studies have suggested that the parts of the brain that control thinking and memory are larger in volume in people who exercise than in people who don’t. Tests have shown that with mild exertion people perform better on tests of attention and memory and walking regularly increases the increases the volume of the hippocampus (a brain region crucial for memory) and elevates levels of molecules that both stimulate the growth of new neurons and transmit messages between them. even the abundance, survival, and overall health of new brain cells.

Exercise improves our thinking skills and memory through stimulating physiological changes such as reducing insulin resistance and inflammation, along with encouraging the production of chemicals that affect the growth of new blood vessels in the brain (known as growth factors), and myokines, which act as natural antidepressants.

Movement has a protective effect on our brain, which makes it less susceptible to cognitive decline and neurodegenerative disease.

Couch Potato Syndrome

An American term for a sedentary person whose predominant leisure time consists of lying on a couch, watching television or scrolling through the internet.

In 2019, UK adults spent 9 hours and 38 minutes a day consuming media including 1 hour 50 minutes on social media. They spent an average of 12 hours a week spent watching TV, compared with 1 hour 30 minutes being physically active. That’s roughly 624 hours a year (26 whole days), compared with 78 hours (3 whole days) of physical activity.

Watching TV Is A High-Risk Activity

Much as people would love to believe there’s nothing they can do to change their fate; study after study shows clearly the connection between genetic and epigentic changes related to cognitive decline is dependent upon lifestyle factors, many of which we have an ability to change. These are known as modifiable risk factors, aspects of your life where you can take measures to change, including diet, exercise, social interaction, how much time you spend in your comfort zone repeating the same things over and over or if you step outside of it to challenge yourself - physically or mentally.

If regular brain exercise improves cognitive function, then it stands to reason that the opposite is also true - if you don’t use your brain then you lose cognitive function.

A 25 year study conducted by the U.S. National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health, looked at whether there were any long-term effects of watching TV. The researchers followed 165,087 adults between 50 and 71 years old, beginning in 1994 and ending in 2011. The researchers found those who watched more than five hours of TV per day had a 28% greater incidence of death during the period compared to those who watched less than 3 hours per day.

Another study, published in 2002, claimed that 68% of American high school students don’t participate in daily physical education. Unlike the generation who are middle-aged and older, these children are growing up sedentary from birth, so it’s likely that the damaging effects of being sedentary will be even more noticeable, from an earlier age than the current elderly population. Movement and exercise are known to increase the baseline of new neuron growth - we grow more brain cells when we move than when we don’t and this leads to better memory, increased cognition and reduces the chances of depression.

Society is fixated on the physical body and whether it is ‘in shape’, but nary a peep is heard about the condition of our brain. Movement acts on the body through affecting (amongst other things) our bones, muscles, and cardiovascular system and acts on our brain by strengthening areas like the corpus callosum, basal ganglia and cerebellum and strenuous physical exercise stimulates the growth of new neurons in the hippocampus, the part of the brain that is critical for memory.

Without stimulation or novelty, cognitive function declines and people who participate regularly and actively in lifelong activities (be they intellectual, social or cultural) experience fewer cognitive complaints, perform better on formal cognitive tests and are less likely to develop neurodegenerative disorders.

The risk of cognitive decline cannot be laid squarely at the door of our inherited genetics; study after study shows how important modifiable risks factors are as well. These are lifestyle factors that can be controlled to a certain extent in order to avoid dying from a lifestyle or degenerative disease when you age. High blood pressure, raised cholesterol, diabetes, smoking, drinking alcohol, physical inactivity, obesity, unhealthy eating, social deprivation are all modifiable depending on our lifestyle and all play a part in shaping our risk profile.

Inactivity Leads to chronic health issues

Research published in 2019 estimated that direct healthcare costs incurred as a result of prolonged sedentary behaviour causes a considerable burden to the NHS. They claim that 69,276 UK deaths might have been avoided in 2016 and calculate that, for 2016-2017, the total NHS costs attributable to prolonged sedentary behaviour were £700 million. This was divided up into costs for cardiovascular disease (£424 million), type-2 diabetes (£281 million), colon cancer (£30 million), lung cancer (£19 million) and endometrial cancer (£7 million).

Study author, Dr Mussap said: “Uninterrupted sitting constitutes a substantial risk to physical and mental health. There are known associations with poor musculoskeletal health, a range of cardiovascular diseases and even cancer. There is a common yet incorrect belief that prolonged workplace sitting is not problematic if a person is physically active during their recreational time”.

The effects caused by prolonged sitting cannot be undone by being active for a short amount of time a day, yet for many they assume that they can offset the costs of being sedentary by a small burst of high-impact cardio. These people have been termed ‘active couch potatoes’ because they meet the demand for physical activity but still sits down for long periods of the day. The workplace has, until recently, not been part of the discussion when it comes to maintaining health and moving throughout the day; yet, depending on the culture of your workplace, it may not be socially acceptable to move much. The culture of workplaces will need to be addressed in order for meaningful change to happen and an acknowledgement that all forms of sedentary behaviour form a chronic health risk.

Conclusion

Modern life has become structured in a way that makes it very easy to avoid movement; we sit in cars to travel, sit at our desks for work and come home to sit in front of the TV to ‘relax’. The downgrading of real-world experiences in favour of virtual ones has been accelerated due to Government Covid-19 restrictions and it’s difficult to see how we’ll reverse that trend as virtual reality is on the horizon and shopping in the high street is an unpredictable and unpleasant experience (thanks to parking fees, clone towns with the same shops and inconvenient opening times).

Our mind may have adapted to this de-physicalised world but our bodies are still physiologically hunter-gatherers; how this tension will resolve itself is yet to be known. An optimal human life is one where we are active throughout all of our life, from birth to death, and our increasingly sedentary lifestyles will correspond to chronic health problems earlier in life than we have seen with the current eldery population, who enjoyed very physically active childhoods. If people do start getting chronically ill younger in life then this will cause a huge burden on the healthcare system and, in turn, the taxpayer will be required to pay higher taxes to pay for treatments and interventions.

Plenty of evidence shows how movement increases the number of brain cells and imaging sources, anatomical studies, and clinical data shows that moderate exercise enhances cognitive processing. This may also work in reverse; if we pursue physical inactivity then we lose a lot of the potential cognition and brain power gained through movement. The problem is that we’re not sea squirts and some form of movement is a non-negotiable if we want to maintain any kind of quality of life - in one study it found that a lack of exercise together with increased television watching doubles your risk of cognitive impairment later on:

“High television viewing and low physical activity in early adulthood were associated with worse midlife executive function and processing speed. This is one of the first studies to demonstrate that these risk behaviors may be critical targets for prevention of cognitive ageing even before middle age.”

The sea squirt analogy is more symbolic than literal; nevertheless the sea squirt consumes its brain because it has no more need to move.We must change our perception of risk from snowboarders tearing down mountains, to people sitting on the sofa staring at a screen for hours on end. Thomas Sowell wrote ‘the great escape of our times is escape from personal responsibility for the consequences of one’s own behaviour.’ When it comes to health this is true for a certain amount of time, but we only kick the can down the road; eventually the problem we’ve given to our future self becomes our present self.

REFERENCES

Heron L, O'Neill C, McAneney H, et al, Direct healthcare costs of sedentary behaviour in the UK, J Epidemiol Community Health 2019; 73:625-629.

Placebos Without Deception: Outcomes, Mechanisms, and Ethics, Luana Colloca, Jeremy Howick, https://doi.org/10.1016A

Handbook of Categorization in Cognitive Science, 2005

Baillargeon, R., and Graber, M. (1988). Evidence of a location memory in 8-month old infants in a non-search A-not-B task. Dev. Psychol. 24, 502–511.

Lakoff, G. J., and Johnson, M. (1999). Philosophy in the Flesh: The Embodied Mind and Its Challenge to Western Thought. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Fajen, B. R., and Warren, W. H. (2003). Behavioural dynamics of steering, obstacle avoidance and route selection. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 29, 343–362.

Smith, L. B., and Gasser, M. (2005). The development of embodied cognition: six lessons from babies. Artif. Life 11, 13–30.

Runeson, S. (1977). On the possibility of “smart” perceptual mechanisms. Scand. J. Psychol. 18, 172–179.

Bingham, G. P. (1988). Task-specific devices and the perceptual bottleneck. Hum. Mov. Sci. 7, 225–264.

McBeath, M. K., Shaffer, D. M., and Kaiser, M. K. (1995). How baseball outfielders determine where to run to catch fly balls. Science 268, 569–573.

Thelen, E., Schöner, G., Scheier, C., and Smith, L. B. (2001). The dynamics of embodiment: a field theory of infant perseverative reaching. Behav. Brain Sci. 24, 1–86.

UK adults spend 12 hours a week watching on-demand TV but only 90 minutes exercising

How Much Time Do People Spend on Social Media?

Embodiment and grounding in cognitive neuroscience

Fancourt, D. & Steptoe, A. (2019) Television viewing and cognitive decline in older age: findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Sci Rep, 9, 2851

Hoang TD, Reis J, Zhu N, Jacobs DR Jr, Launer LJ, Whitmer RA, Sidney S, Yaffe K. Effect of Early Adult Patterns of Physical Activity and Television Viewing on Midlife Cognitive Function. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Jan;73(1):73-9. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2468. PMID: 26629780; PMCID: PMC4755299.

Clark, B. K., Sugiyama, T., Healy, G. N., Salmon, J., Dunstan, D. W., Shaw, J. E. & Zimmet, P. Z. (2010). Socio-Demographic Correlates of Prolonged Television Viewing Time in Australian Men and Women: The AusDiab Study. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 7, 595-601

Keadle, S.K., Arem, H., Moore, S.C. et al. Impact of changes in television viewing time and physical activity on longevity: a prospective cohort study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 12, 156 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-015-0315-0

Katrien Wijndaele, Søren Brage, Hervé Besson, Kay-Tee Khaw, Stephen J Sharp, Robert Luben, Nicholas J Wareham, Ulf Ekelund, Television viewing time independently predicts all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: the EPIC Norfolk Study, International Journal of Epidemiology, Volume 40, Issue 1, February 2011, Pages 150–159, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyq105

Lifestyle change and the Prevention of cognitive Decline and dementia

Wajman JR, Mansur LL, Yassuda MS. Lifestyle Patterns as a Modifiable Risk Factor for Late-life Cognitive Decline: A Narrative Review Regarding Dementia Prevention. Curr Aging Sci. 2018;11(2):90-99. doi: 10.2174/1874609811666181003160225. PMID: 30280679.

National Institute for Mental Health in England (2005) Facts for champions, London: Department of Health, p.11.

What are the most common misconceptions about furniture free? Well these are my top three!