Wellness Banking

Wellness banking the newest idea to encourage people to spend responsibly all the while improving their physical health with the use of wearable devices that monitor your activity. Personal responsibility takes another hit in a new report published by Deloitte; every time you make a healthy choice your bank will rewards you with discounts, vouchers or cashback. This comes hot on the heels of Boris Johnson and his magic money tree; he is considering giving out shopping vouchers for losing weight and has allocated £100 million of taxpayers money for slimming schemes.

The report also told financial companies there was a ‘sizeable opportunity’ for them to profit from health and wellness initiatives, especially if they presented these as ‘enablers of social good’. The powerful incentive for proving you lead a virtuous, healthy, non-sedentary lifestyle will lead to reduced premiums and other perks. As Vitality put it: ‘The healthier you get, the more we’re able to offer you. It’s a virtuous circle that’s good for you, good for us, and good for society.’

Some new research from Coventry Building Society has shown that nearly 90% of those who exercise more regularly, at least once a week or more, are more likely to put some money away each month. However, of those who don’t exercise, fewer than three in every four (74.2%) have a regular savings habit. Irrespective of the ridiculous simplification of extracting meaning from this, expect more tenuous links between health and finances to be made as justification for these wearables. Remember, correlation doesn’t equal causation - for instance, someone on a higher income is more likely to exercise and save money than someone on minimum wage. Income is one main connections to health and is seldom mentioned in the corporate media and rarely is factored into any of these schemes.

Such simplistic rhetoric taps right into the heart of our desire to contribute to society, to do the right thing for the greater good. There’s little conversation about who decides what constitutes health, what that entails and whether anyone will stand to profit from defining those terms. Will you be punished for ignoring the highly questionable food pyramid and opting to intermittently fast or live on a carnivore diet?

If you’re not paying for the product, you are the product

In America, data brokers aggregate and sell an average of 3,000 pieces of data per person; information gleaned from retailers, social networks and financial firms that, collectively, paint an incredibly detailed picture of people’s lives. Detailed and highly lucrative; the more information there is about you, the more money there is to be made.

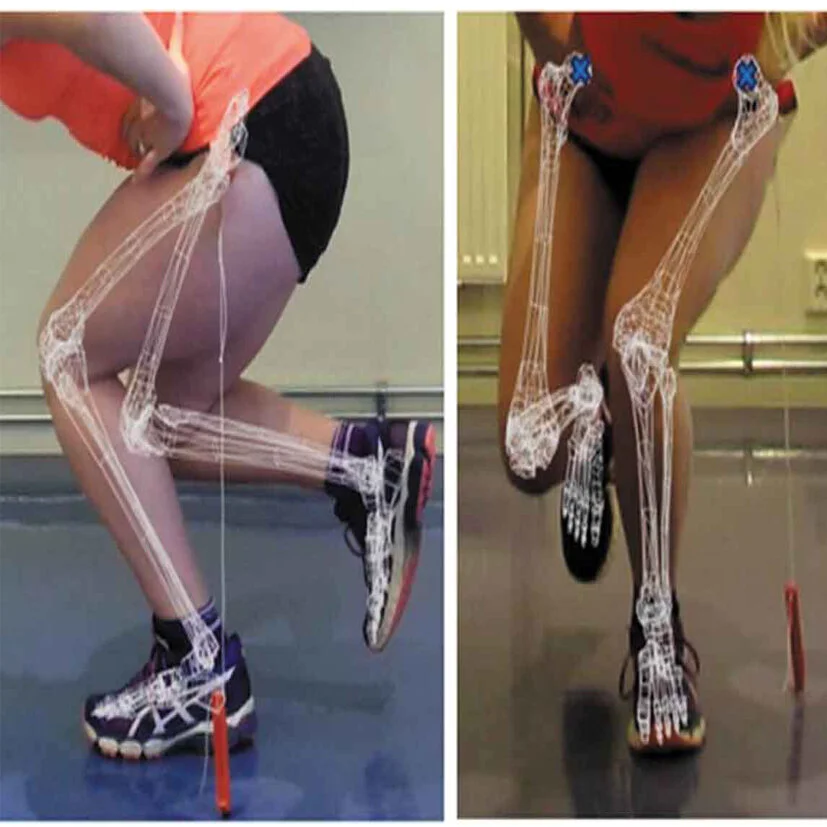

When it comes to matters of health, insurance providers get very interested - and many see fitness trackers as a way to sell more premiums. A recent survey revealed that 63% of insurance executives seeing wearables having a ‘significant impact’ on the industry, and that their use in premiums would be ‘wide-spread’ in just two years. Heath insurers have started subsidising Apple watches and users can then bring down how much they pay back each month by completing activity goals set by the insurance company - monitored and verified by Apple.

Over the past few years, mobile devices and wearables have been passively or actively tracking a huge amount of personal data about us. Equipped with sensors from heart-rate tracking to GPS, they routinely capture all kinds of metrics and store them whether we like it or not. Companies can take advantage of this by including health monitoring within a finance app - which allows them to access information about our spending habits, too. Data like this helps banks understand our saving habits and gives them valuable insights into which people are likely to be the best customers. The Holy Grail is glucose monitoring because of the insights that could give into what someone has eaten which is a crucial data point for insurers, since diet has a far greater impact on health than activity.

Data is the new oil

To benefit from wellness banking you must share more personal data with your bank than ever before and allow it to track your movement, exercise routine and diet; the more you’re willing to share, the more rewards you’ll receive.

The rise of ‘open banking’ is the system of allowing access and control of consumer banking and financial accounts through third-party applications. Open banking allows customers to give permission for the bank to share data with other banks or organisations - just as you can access your data across a range of places, so can your bank.

It’s becoming increasingly easy for banks to profile our spending habits now we pay for so much by card or smartphone. Some banks are connected to loyalty cards which increase the amount of data available about you, on top of the data about your shopping habits, purchases and normal card spending. Accurate profiles can be built up about us and our habits and this data can be sold or shared with our companies such as advertisers. Banks claim to only use this information to spot fraud and flag up an account if a card is being spent somewhere out of the ordinary. Whilst this may be true, such information can also be used for profiling customers and, in an world where companies stand to profit, convenience will always be presented to us as worth the cost of giving away our privacy. After all, we may even be rewarded for it, though the rewards are likely to be worth significantly less than these companies stand to make with all of our the data.

Hot on the heels of data-gathering comes AI (Artificial Intelligence), a huge subject that warrants further discussion in the future. It is hard to over-emphasise how much of a paradigm shift this will soon create; already companies are discussing things such as personalised pricing of insurance (sometimes referred to as behavioral premium pricing or dynamic pricing solutions) which uses machine learning to find data patterns. These patterns are created through analysis using a variety of sources, such as your loyalty cards, in order to predict future behaviour.

Confidential data such as diagnosis, medical reports and images are already being used by AI to educate itself and, over time, this machine learning will diagnose the onset of illnesses and warn people to take precautions and necessary steps to mitigate the consequences. There’s not much discussion about what the consequences may be financially, economically or socially if we choose to ignore the AI’s advice.

AI is sufficiently sophisticated to be able to analyse large amounts of medical data about someone, accumulate it in a single place and use the data to analyse and predict previous and present health problems. A study published in February 2020 took data from routine CMR scans, compared them with the patient’s outcomes and the results showed how the AI was better than human doctors at predicting a patients’ chance of death, heart attack, heart failure and stroke.

Ethical Concerns

It is hopelessly naive to assume all these companies have our best interests at heart just because they say they do in their advertising. Their primary objective is to make a profit and there is a lot of profit to be made in data. They may claim that the data is being collected for a single purpose - optimising your health - but it could easily be used for something else such as targeted advertising. Vikram Renjen, the Senior Vice President of Insurance for Sutherland notes: ‘With supplemental GPS data, wearables could monitor and report on compliance to the rehabilitation protocol of a disability claimant. Improved compliance would shorten the time until return to work.’

What happens if your bank or insurance company gets hacked and mountains of your data is leaked?

If the aim of an insurance company is to cut healthcare costs in exchange for financial rewards then does the end justifies the means? In other words, will these companies be setting you inappropriate goals just to get you to hit your target figures? How will they tailor workouts to your personal situation and will they punish you for not complying with theirs? What if you are injured due to over-training from the goals set by the company?

Perhaps all your data makes you undesirable to be insured. What then? Will you have to change your entire life to fit what these companies deem healthy?

There are more questions that answers in this ever-evolving technological world we’re living in. Do we want to live in a world where we are bribed like children to do things like taking care of ourselves? Isn’t that what we should be doing already?

All my questions point at a deeper problem in our society where we increasingly come to expect others - often the ‘benevolent’ Government or for-profit companies - to take care of us and act with our best interests at heart. Such an infantilised view of the world will only make us vulnerable to exploitation. Instead, it would be wiser to look towards voluntary solutions to tackle societal issues rather than coercive ones.

REFERENCES

Banking on healthcare: The new health and wellness frontier

Brits who get in shape are more likely to have their savings in shape too

Kelly MP, Barker M. Why is changing health-related behaviour so difficult? Public Health. 2016 Jul;136:109-16. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2016.03.030. Epub 2016 May 13. PMID: 27184821; PMCID: PMC4931896.

Global Wellness Trends Report: The Future of Wellness 2021

All online junk food ads to be banned in tough anti-obesity proposal

Wearable Tech Is Plugging Into Health Insurance

Smartwatches and health insurance: Good or bad?

Physical activity tracking in private insurance

Step and save: The truth about wearables and health insurance

63% of insurers believe wearables will transform industry – here’s how

The worrying potential of wearable data

Vlaev, I., King, D., Darzi, A. et al. Changing health behaviors using financial incentives: a review from behavioral economics. BMC Public Health 19, 1059 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7407-8

From Credit Scores to “Behavioral Scores”: What Numbers Say About You

AI measures blood flow to predict death, heart attack—and is more accurate than humans

The Prognostic Significance of Quantitative Myocardial Perfusion, An Artificial Intelligence–Based Approach Using Perfusion Mapping, Kristopher D. Knot, Andreas Seraphim, Joao B. Augusto, Hui Xue, Liza Chacko, Nay Aung, Steffen E. PetersenJackie A. Cooper, Charlotte Manisty, Anish N. Bhuva, Tushar Kotecha, Christos V. Bourantas, Rhodri H. Davies, Louise A.E. Brown, Sven Plein, Marianna Fontana, Peter Kellman, James C. Moon, Originally published 14 Feb 2020 https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044666 Circulation. 2020;141:1282–1291

Bank refuses to release mortgage for woman deemed at higher Covid risk

What are the most common misconceptions about furniture free? Well these are my top three!