Will Labelling Foods With The Amount Of Physical Activity Needed To Burn Off Calories Work?

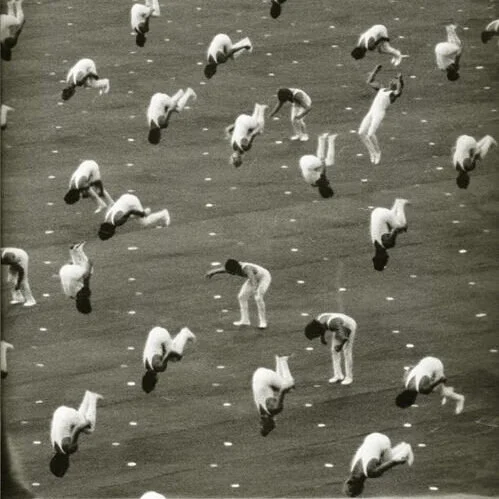

The Royal Society for Public Health has called for ‘activity equivalent’ calorie labelling to replace the current food labelling system. The idea behind ‘Physical activity calorie equivalent (PACE)’ food labelling is that a series of easily recognisable icons would be used to represent types of physical activities, such as walking, running, cycling, and swimming. The icons would be combined with a number representing the number of minutes you would need to spend doing that activity to burn off the calories in the food or drink item. The thinking behind this idea is that by giving people an immediate link between the energy content in a food or drink product and physical activity, people might think twice if they were aware of how much exercise is needed to burn off different types of food and this is a way to reduce obesity.

Food for thought:

29% of UK adults classed as obese

20% of UK 10 year olds classed as obese

10,660 hospital admissions in the UK directly attributable to obesity in 2019

711,000 hospital admissions in the UK where obesity was a factor in 2019

Estimated annual social care costs of obesity to local authorities is £352m

The government estimates that treatment of obesity-related conditions in England costs the NHS £6.1 billion each year

The overall cost of obesity to wider society is estimated at £27 billion per year

Annual spend on the treatment of obesity and diabetes is greater than the amount spent on the police, the fire service and the judicial system combined

Physical activity calorie equivalent or expenditure labelling (PACE)

A 2015 poll carried out by Populus found 41% of UK adults found current front-of-pack information confusing and there is little evidence that the current information on food and drink packaging changes peoples behaviour. The Chief Executive of the British Medical Journal wrote an article expanding on the benefits of labelling:

“The objective is to prompt people to be more mindful of the energy they consume and how these calories relate to activities in their everyday lives, and to encourage them to be more physically active…Such information needs to be as simple as possible so that the public can easily decide what to buy and consume in the average 6 seconds people spend looking at food before buying…Calculating the exercise equivalents probably wouldn’t be all that difficult because companies could use an algorithm based on an ‘average person’ for different food items.”

There are a few things that will need to be addressed before the Government spends huge amounts of taxpayers money on a potentially unsuccessful endeavour. Firstly, there is already plenty of information out in the world helping people understand what is and isn’t good for them - so there may be other, more invisible reasons why they choose unhealthy food. It could be past trauma, current depression and emotional eating, none of which will likely be curbed by seeing how much exercise they’d need to do, it may even increase their misery as they fail to heed the advice. There is also the question of advertising blindness - in an age in which we are subject to an onslaught of between 4,000 and 10,000 advertisements each day, will we be paying that much attention to food packaging?

How will the manufacturers be transparent and clear with their packaging when the products they are selling are inherently unhealthy? They are sure to sugar-coat this in the best possible light as they always have done (see my post about Healthwashing).

I can forsee exercise equivalent labelling being used by people to trade off and justify their consumption of processed foods - if they’re going for a run then they can burn off the snack they ate earlier in the day. The other issue is that all calories are not equal, despite what many diet groups would have you think; it’s mental gymnastics to think of food in terms of simple equations, trade-offs and cheat days instead of simply following a nutrient dense diet. On top of this is the fact the numbers themselves would be based off of averages and not take into account any factors such as peoples age, their build, height or intensity of exercise.

What it takes to burn off:

An apple (93 calories):

21 minutes of brisk walking or 13 minutes of running

A 330ml can of Coca-Cola (139 calories):

32 minutes of brisk walking or 20 minutes of running

A 48g Snickers bar (245 calories):

56 minutes of brisk walking or 35 minutes of running

A 50g bowl of cornflakes served with semi-skimmed milk (263 calories):

An hour of brisk walking or run for 37 minutes

What is the role of the Government in public health?

There is a general assumption that it is the Government’s duty to step in and do something wherever there is a problem. At the start of the 20th century, Governments became increasingly involved in their citizens private lives, with the people bearing this cost through increased taxation. Fast forward to today where we live in a more regulated society than at any time in history and the Government has monopolised many aspects of our lives and made it incredibly difficult to operate outside their sphere of influence. Activities or professions that used to be completely free until a few decades ago now require permission from the Government in the form of myriads of authorisations, licenses, insurances and permits that can be revoked if you don’t follow their rules. This undermines personal autonomy and has infantilised us all, with the irony being the Government has far exceeded the number of rules with a peak net benefit as well as the uncomfortable fact that Government intervention doesn’t produce prosperity.

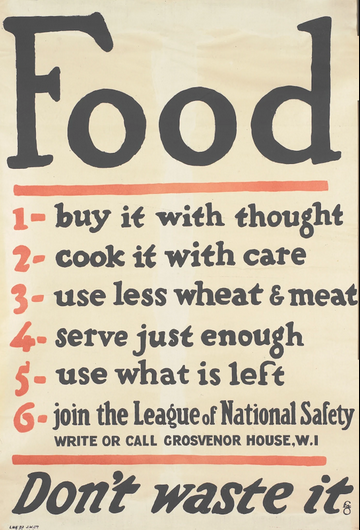

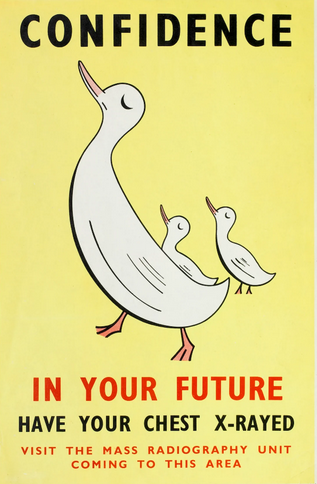

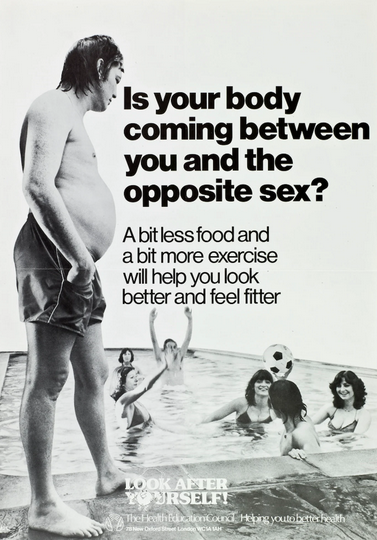

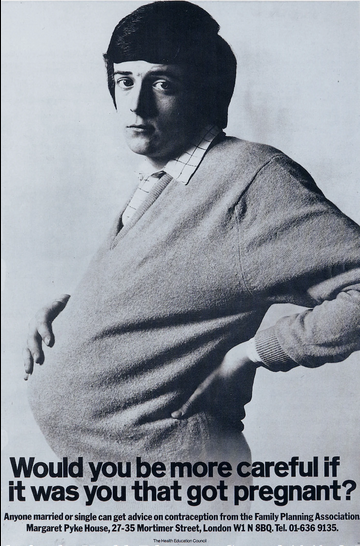

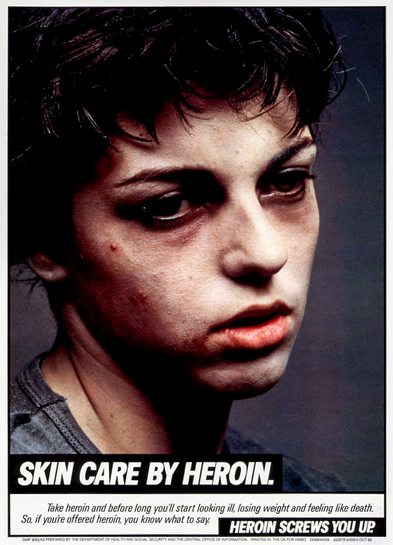

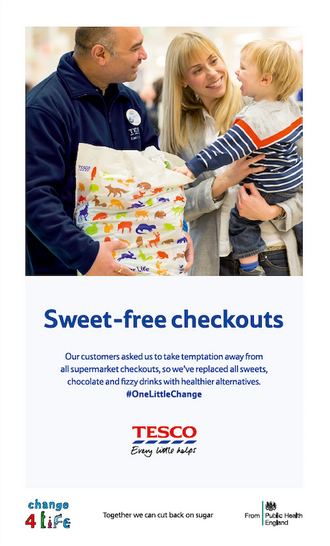

Rachel Louise Moran posits the concept of the ‘advisory state’ which is the the use of Government research, publicity, and advocacy aimed at achieving citizen support and voluntary participation to realise social goals. Instituted through outside agencies, posters, glossy pamphlets as well as legislation, the advisory state is the Government out of sight yet intimately present in the lives of citizens. Action is always done under the pretext of care and paternal concern for us, these subtle ways serve to mask governmental interference in personal decisions about diet and exercise.

Alongside Public Health campaigns, the Government also has its finger in Agricultural subsidies, which, even though these are not the foods the government tells us to eat with their dietary guidelines, they’re the foods the government makes cheap. Food subsidised by the Government may sound healthy, except that they’re typically not eaten in their whole-food form; rather, they’re turned into cattle feed or refined and processed fatty foods. Taxpayers currently pay £233 per hectare to farmland which, in theory, sounds like a good idea. Except that, according to George Monbiot writing in The Guardian:

It is also arguably the most regressive transfer of public money in the modern world. Farmers are paid by the hectare for owning or using land; so the more you have, the more you get. While in the UK benefits for poor people are capped at £20,000 (outside London), these benefits for the rich are uncapped. Some landowners receive £1m or more. You don’t even have to live in the EU to take this money: you just have to own land here. Among the benefit tourists sucking up public funds in the age of austerity are Russian oligarchs, Saudi princes and Texas oil barons. Yet even farmers have been hurt by these payments. European subsidies have helped turn farmland into a speculative honeypot, making it highly attractive to City financiers. The price of land has more than doubled since payments by the hectare were introduced, pushing it out of reach of most farmers.

Big Government affects us all because it decides how it thinks best to spend and allocate our money. In 2019, the tax burden in the UK was at a 50-year high: taxes reached 34.6% as a proportion of GDP in 2018-19, the highest level since 1969-70 (it will most certainly surpass this in the wake of Covid-19).

Healthism weighs in

Many of the public health interventions are focused on the individual taking full responsibility for their health, however it must be noted that the environment around us has a huge impact on the decisions we make. A food desert is defined as ‘an urban area in which it is difficult to buy affordable or good-quality fresh food’ and, in most towns and cities in the UK, you’ll find it significantly harder to opt for healthy food and drink options. You will have to go out of your way to find them and you’ll only be greeted by a few token healthy choices in petrol stations or corner shops - almost everything will be pre-packaged and not freshly made on-site. If we use the philosophy of ‘make the wrong thing hard and the right thing easy’, then this isn’t what is happening where it is a challenge to make healthy food choices within a limited budget. If it is time-consuming, inconvenient and expensive to choose the healthy option, can all responsibility be placed on the individual?

Robert Crawford published an essay in 1980 titled ‘Healthism and the Medicalization of Everyday Life,’ in which he argues:

“Healthism situates the problem of health and disease at the level of the individual. Solutions are formulated at that level as well. To the extent that healthism shapes popular beliefs, we will continue to have a non-political, and therefore, ultimately ineffective conception and strategy of health promotion. Further, by elevating health to a super value, a metaphor for all that is good in life, healthism reinforces the privatization of the struggle for generalized well-being.”

Australian researcher Dorothy Broom, in an essay titled ‘Hazardous good intentions: unintended consequences of the project of prevention,’ writes that:

“Theories of health and disease prevention are redolent with terms that appear to signify the centrality of individual behavior. Words such as ‘personal habits’, ‘choice’ and ‘lifestyle’ are readily applied to people who are apparently solitary individuals….Most health risk factors are distributed according to socioeconomic position: people with less wealth, lower incomes, worse jobs, less education, and living in poor neighborhoods are more likely than their counterparts to manifest health risks and impaired health status.”

Conclusion

While PACE labelling might be an extra tool to help people consider making better food choices, it’s not the complete answer to a healthy diet and is unlikely to singlehandedly tackle the UK’s obesity and lifestyle disease epidemic. There are a complex mix of factors that contribute to people choosing to eat significant amounts of ultra-high processed foods and we must place the individual within the context of their food environment to have a hope of treating the cause and not the symptom. As radical as it sounds, perhaps if we concentrate more on the carrot of accessible, affordable and healthy food instead of the stick of taxes, fines and punishment, this might garner positive results.

Despite the NHS spending huge amounts of taxpayer money of healthcare and prevention has failed to diminish health inequalities with Britain often being dubbed ‘the sick man of Europe’ and a 2013 study noted that despite six decades of free medical care and widespread health campaigns, Britons are among the unhealthiest people in Western Europe. International researchers analysed the country’s rates of sickness and death from 1990 to 2010 in comparison to those of 15 other Western European countries in addition to Australia, Canada and the U.S. Experts described the U.K. results as ‘startling’ and said Britain was failing to address underlying health risks in its population, including rising rates of high blood pressure, obesity and drug and alcohol abuse.

Overall, the U.K. was 12th for healthy life expectancy, with most Britons expected to live 68.6 years in good health. The United States came in 17th out of 19 countries with 67.9 years. Spain topped the charts with a healthy life expectancy of 70.9, while Finland came last, with most Finns likely to live 67.3 years in good health. Australia ranked 3rd with 70.1 years, while Canada was 5th with 69.6 years. In terms of years of life lost to health conditions, Britain ranked just above last place for serious respiratory infections, preterm birth complications, and breast cancer.

“There are two kinds of people in this world.

Those who think the government is doing things in their best interests and those who think.”

History has shown us time and time again that when politicians, either on behalf of pressure groups or through sheer inability to consider all the facts, interferes with the free working of a country’s economy, they set in motion forces which may be as disastrous as they are immeasurable. In 1984 New Zealand scrapped all agricultural subsidies which freed farmers to produce what people really want, and to do so in an efficient way that could turn a profit. Since the reforms, New Zealand farmers have cut costs, diversified their land use, and developed new products with productivity in agriculture growing faster than New Zealand economy as a whole. Not to mention the price of land, artificially inflated due to subsides, plummeted enabling many more people the opportunity to begin a land-based business.

Government intervention in our personal life is accepted by most people as a necessary evil, yet this social contract brings up uncomfortable questions. If the financial and economic cost is so high for treating lifestyle diseases and constitutes a significant portion of the NHS budget, then does every taxpayer have a responsibility to be healthy? After all, this is the era of ‘protecting the NHS’, so does that extend out to preventable illness as well as occasional respiratory ones?

Ultimately, is it reasonable or sensible to assume a Government can act in our best interests? 65 million people will have different opinions on what those best interests are and how they should be implemented. Are we so naïve to assume these bureaucrats will act benevolently and administer eye-watering amounts of money fairly, equally and free of corruption? As the Government assumes a more and more proactive role in our daily lives, we risk becoming infantilised and shirking responsibility for our own health because we now think it is our right to have free, unlimited healthcare borne by the taxpayer, irrespective of whether we are holding our side of the bargain and maintaining our health. We are unrecognisable from our Great-Grandparents and we now expect our Government to solve our problems; we don’t want to take personal responsibility or do anything to improve our lives. Yet this Faustian pact was always going to come with unintended consequences.

REFERENCES

Food should be labelled with the exercise needed to expend its calories, BMJ2016; 353 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i1856 (Published 06 April 2016) BMJ 2016;353:i1856

Capewell Simon, Lilford Richard. Are nanny states healthier states? BMJ 2016; 355 :i6341

Platkin, C., Yeh, MC., Hirsch, K. et al. The effect of menu labeling with calories and exercise equivalents on food selection and consumption. BMC Obes 1, 21 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40608-014-0021-5

Daley AJ, McGee E, Bayliss S, Coombe A, Parretti HM. Effects of physical activity calorie equivalent food labelling to reduce food selection and consumption: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled studies. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2020 Mar;74(3):269-275. doi: 10.1136/jech-2019-213216. Epub 2019 Dec 10. PMID: 31822568.

Dorothy Broom (2008) Hazardous good intentions? Unintended consequences of the project of prevention, Health Sociology Review, 17:2, 129-140, DOI: 10.5172/hesr.451.17.2.129

Crawford R. Healthism and the Medicalization of Everyday Life. International Journal of Health Services. 1980;10(3):365-388. doi:10.2190/3H2H-3XJN-3KAY-G9NY

What Does it Take to Burn off Calories If I Eat or Drink a Food Item

Nanny or Steward? - King's Fund

Rachel Louise Moran, Governing Bodies: American Politics and the Shaping of the Modern Physique (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018, $49.95). Pp. 216. isbn978 0 8122 5019 0. - Volume 54 Issue 2 - Natalia Mehlman Petrzela

Jasmin Mahmoodi, Ashreeta Prasanna, Stefanie Hille, Martin K. Patel, Tobias Brosch, Combining “carrot and stick” to incentivize sustainability in households, Energy Policy, Volume 123, 2018, ISSN 0301-4215, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.08.037

Seyedhamzeh S, Bagheri M, Keshtkar AA, Qorbani M, Viera AJ. Physical activity equivalent labeling vs. calorie labeling: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018 Sep 14;15(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s12966-018-0720-2. PMID: 30217210; PMCID: PMC6137736.

The growth of government in the 20th century and the importance of debating ideas

A Century of Public Health Marketing

Health matters: obesity and the food environment

Statistics on Obesity, Physical Activity and Diet, England, 2019

Tackling Obesity is Everybody's Business

Report Department of Health & Social Care

The tax burden on households 2019

UK tax burden highest in half a century: TPA report

How Many Ads Do You See in One Day? | Red Crow Marketing

More than a million UK residents live in 'food deserts', says study

'Ultra-processed' products now half of all UK family food purchases

Rich List billionaires scoop up millions in farm subsidy payments

UK Among Unhealthiest Of W. Europe Nations

Agricultural Subsidies in Great Britain - Foundation for Economic Education

What Happened When New Zealand Got Rid of Government Subsidies for Farmers

Common Agricultural Policy: Key graphs & figures

Siegel KR, McKeever Bullard K, Imperatore G, et al. Association of Higher Consumption of Foods Derived From Subsidized Commodities With Adverse Cardiometabolic Risk Among US Adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(8):1124–1132. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2410

What are the most common misconceptions about furniture free? Well these are my top three!