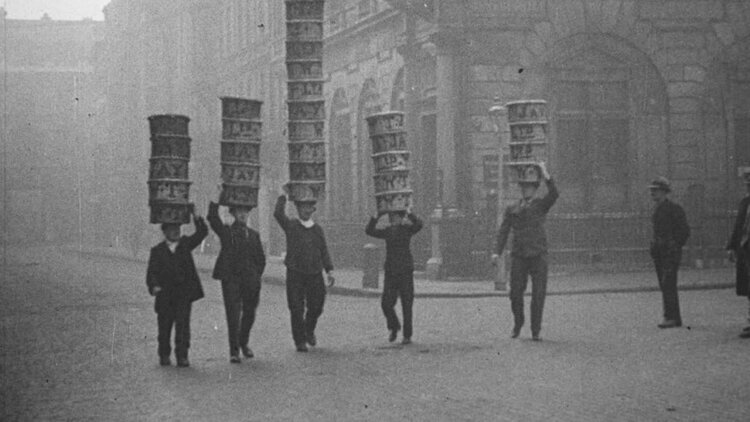

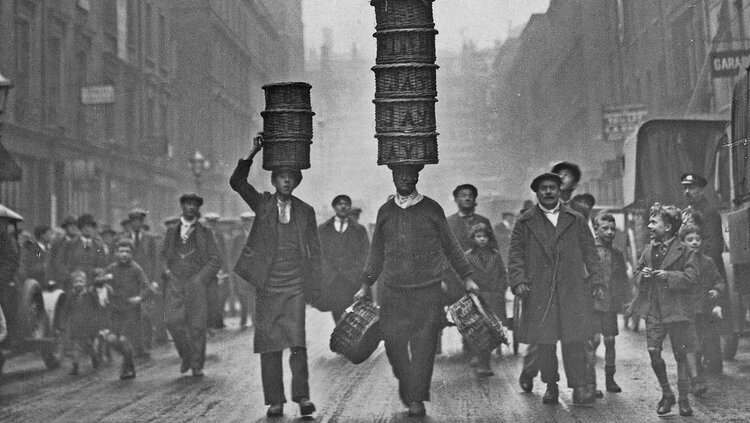

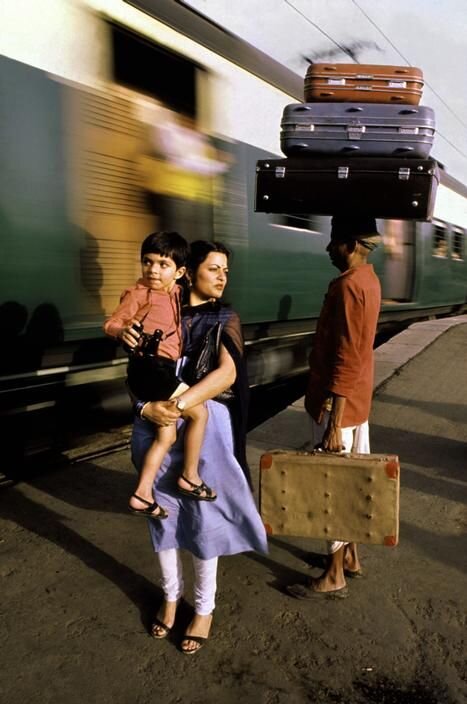

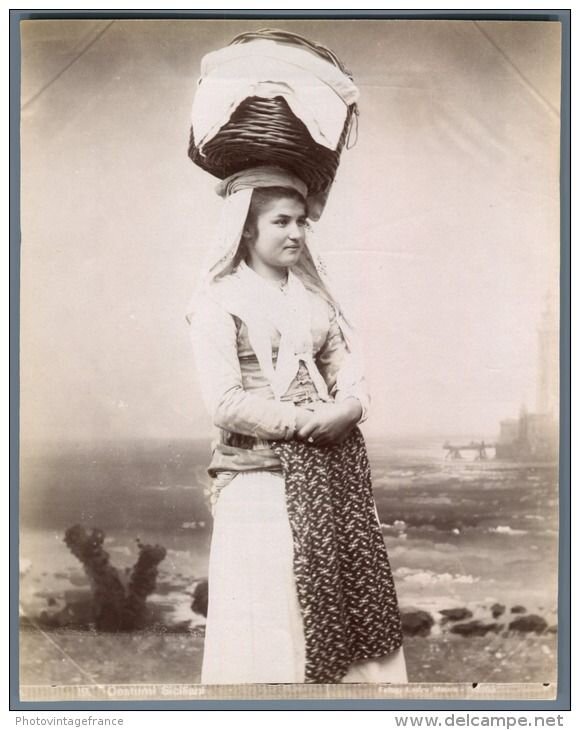

Is Head-Loading a Forgotten Natural Movement Skill?

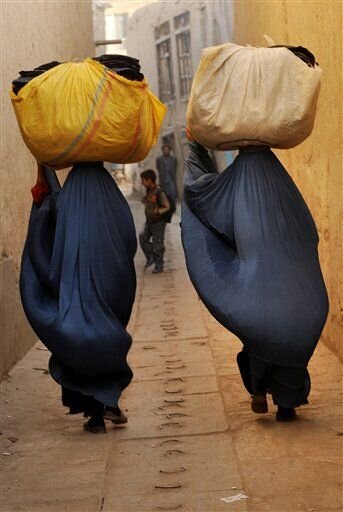

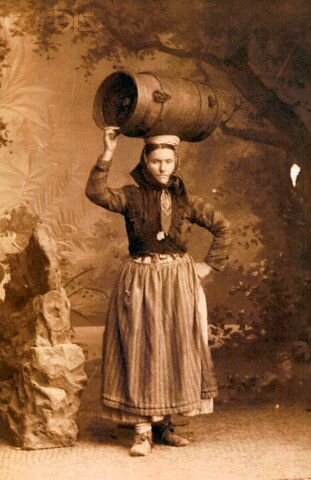

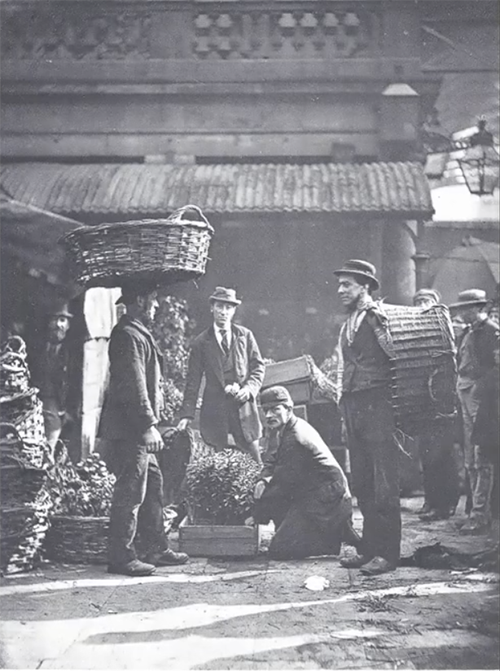

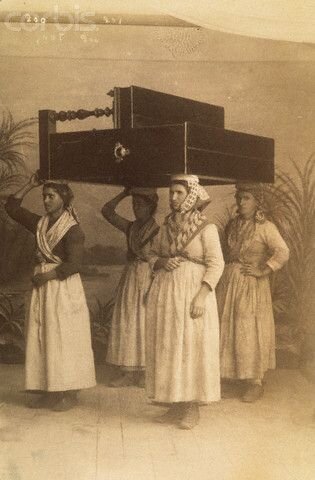

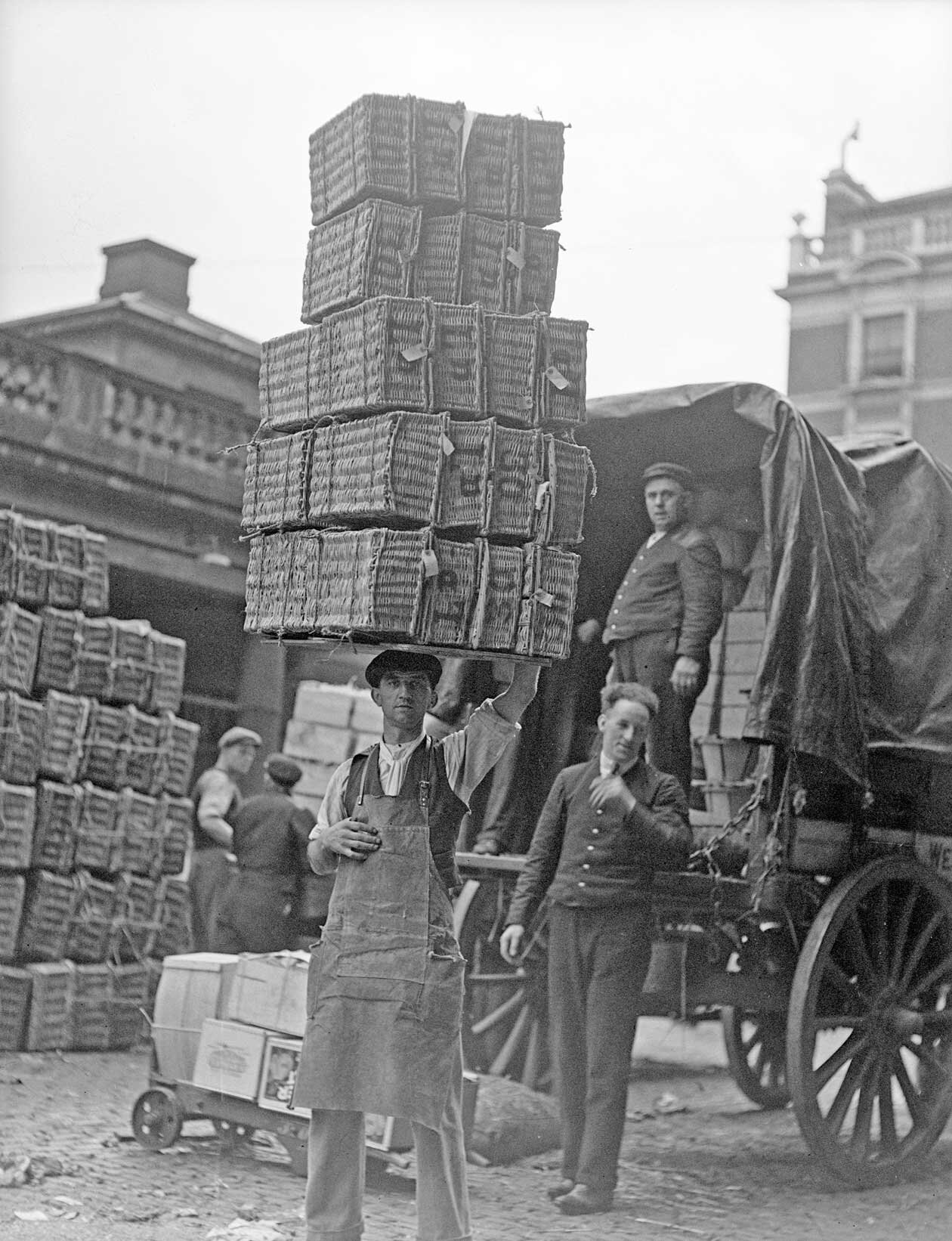

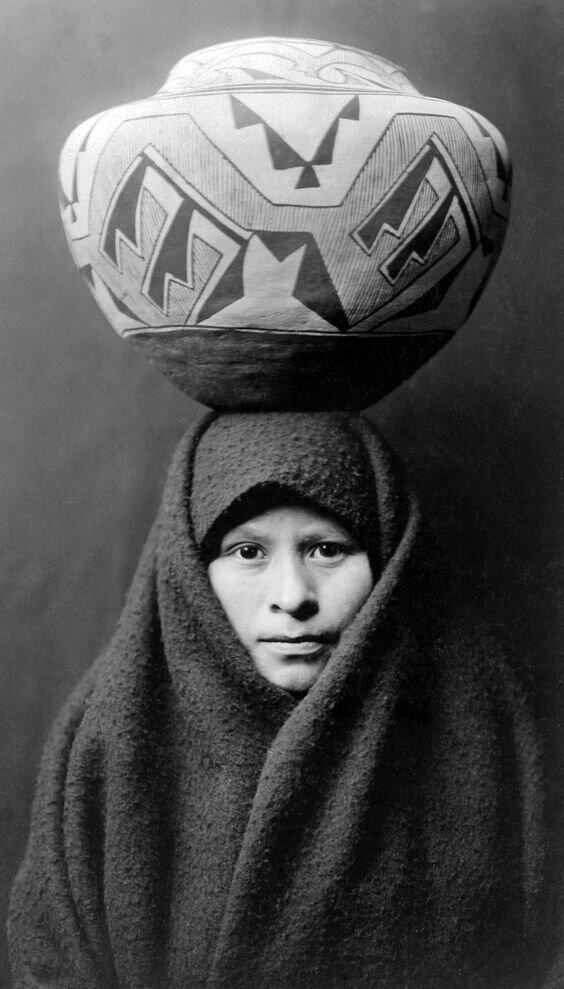

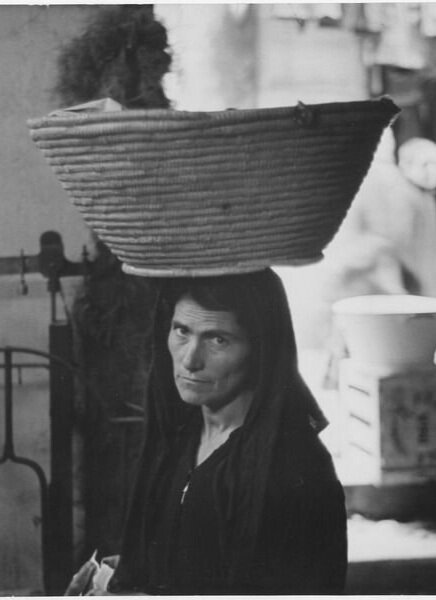

I wrote this post after finding photos of porters in 1920s London carrying baskets on their head as they worked in Covent Garden market, a tradition that lasted from the 1650s until 1974, when the market relocated to the outskirts of the city. Delving a bit deeper, it appears that head-carrying is a universal feature of all cultures, including the West until relatively recently. Despite moving into a more natural movement based lifestyle - as much as is possible in human zoo that makes up the majority of the world - head-carrying seemed barbaric, a sign of oppression and something we were glad to do away with, burdened as it by the connotations of poverty and misery. Yet I wondered if there could be a place for it in modern life and whether it could even be useful as a way to counteract our modern postures, which are shockingly different from those who live in other cultures and our ancestors (see my gallery of images below).

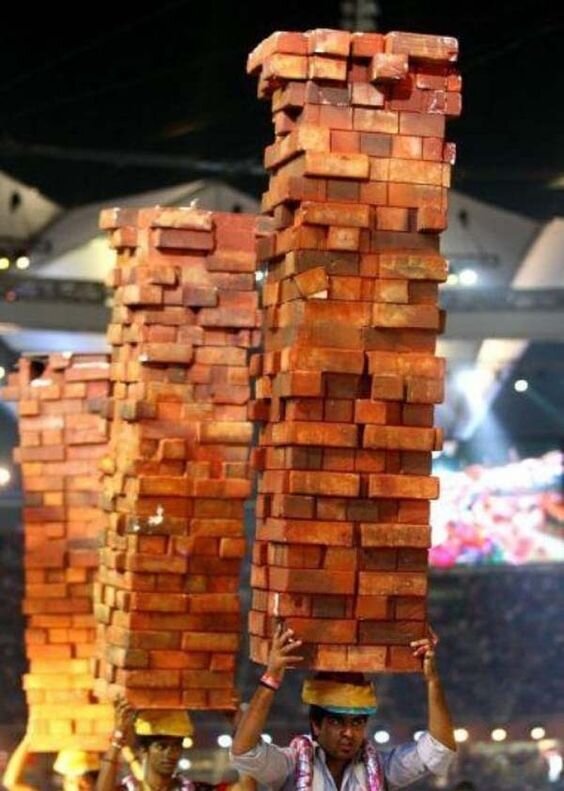

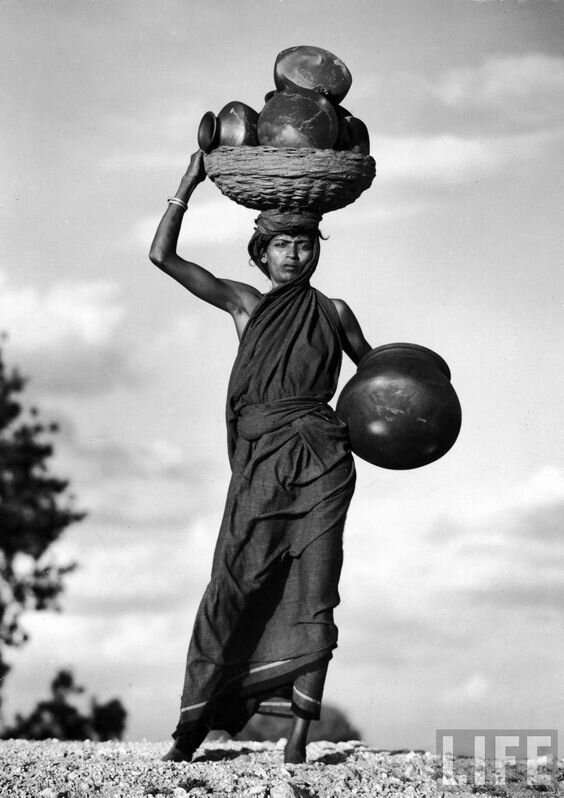

Researchers have found that people can carry loads up to 20% of their own bodyweight, African women carry head-supported loads of up to 60% of their bodyweight far more economically than army recruits carrying equivalent loads in backpacks and Nepalese porters routinely carry loads equally to 200% of their body weight for many days up and down steep mountain footpaths at high altitudes.

Numerous studies show that tumplines, a sling for carrying a load on the back, with a strap that passes round the forehead. and other head-carry techniques are more metabolically efficient than carrying a rucksack because, when used correctly, weight is evenly distributed down the spinal column. Lung capacity isn’t restricted as it can be when using sternum straps, which is important at high altitudes where people are at risk of hypoxia.

‘My back got progressively worse until an expedition to Nepal in 1978. There I noticed how the local people all had huge fillets of muscle running down both sides of their spinal columns. They spend their lives carrying awkward loads in excess of 45kgs over high passes. And they were doing all that carrying with just a crude, plaited bamboo tumpline. I immediately saw the solution to my problem. As long as I had to carry a pack I might as well be exercising my back at the same time! Besides, I’ve never been able to fully utilize modern packs. Hip suspension packs work only on the flats for me. Whenever I try to go even slightly uphill, my hips feel like they are going out of joint. Carrying heavy loads with just shoulder straps leaves me with sore shoulders and back pain at the end of the day. And I can’t breathe with sternum straps.’

- Yvon Chouinard founder of the company Patagonia

In the days before perfectly flat roads and their wheeled counterparts, head-loading was an efficient way to carry awkward shapes such as firewood bundles and buckets of water over rough terrain. Perhaps this connection of the dirt tracks, farm labour and the bad old days has meant we have negative associations to the practice. This is contrasted against the upper classes frequently training their women to be ladylike by walking with books on their heads. The books acted as instant feedback for posture, as slouching would cause the book to fall. The practice was thought to originate in Royal Courts, which valued women’s ability to glide across the room and was a sign that they knew how to behave and would make a respectable wife.

The Baby Boomer generation that came of age in the 1960’s was characterised by a desire for radical change and an intolerance of traditional values. They rejected ‘old-fashioned’ manners, etiquette and common courtesy preferring a more laid-back, familiar approach to life and the gap between the public and private self narrowed. Life became much more casual in attitude, appearance and actions so rigid, aligned postures correlated to a rigid, conformist attitude.

“Most attempts to correct posture are directed toward the spine, shoulders and pelvis. All are important, but, head position takes precedence over all others. The body follows the head. Therefore, the entire body is best aligned by first restoring proper functional alignment to the head.”

The spine acts like a jack

Whenever we are reminded of our bad posture, we stick out shoulders back and presume we’re in alignment. It is much harder to move the head into alignment with the spine when it juts out in front of us as our brain has acclimatised itself to its position and, when conscious intention slips, so too does our posture. The complex movement pattern of being in alignment requires the use of many muscles that may have atrophied in modern bodies, such as the deep stabilising muscles of our neck and down our spinal column. What I find interesting about head-loading is that many different things are happening at the same time, things that would be difficult to consciously do. Weight on the head triggers an automatic response from the body to create a stable axis to most efficiently distribute the weight and alignment is the natural outcome of this. If there is postural dysfunctional through leaning too far back, forward or out to the side, then the body will seek to reduce the centre of mass; the ideal would be as if we were standing in a cylinder.

Roger Perrin was a French physiotherapist who studied head-loading on the mechanics of the body and concluded that the spine acts like a jack. It reacts with a vertical, upwards movement as the head pushes up to counteract the forces of weight. He suggested that as well as the accepted spinal movements (anterior, posterior and lateral flexions, rotation and gliding), another potential movement of the vertebrae should be recognised which he called vertebral erection, the spine lengthens and reduces its curvature.

Joel Carbonnel summarises some key points from Roger Perrin’s research:

Hand-carrying a 15kg weight (for example a suitcase) differs greatly from carrying the same weight on the top of the head. To carry a suitcase by hand requires more effort than to support it on the head. The latter method brings two mechanical advantages: a single axis corresponding to the gravity line of the body, and a small displacement (0.6 to 0.8% of the person’s height).

On average, when someone has to support 15kg on the head, it takes one second for the spine to react in a jack-like manner, and the gain in length is in the order of 12mm. Although this gain is relatively small, the postural and morphological changes are impressive. The average lengthening is 12mm, however there may be greater gain in height for a very slouched individual.

When someone has a load on the top of the head, there is a release of the front muscles and the superficial ones of the back.

Walking with head-supported loads significantly decreases the oscillatory movements of the spine in the three planes – the spine tends to move in a more parallel plane, relative to its long axis (from back to front), while preserving its vertical lengthening response to the load.

Esther Gokhale notes that: ‘I suspect our long anthropological history of head-loading, together with the adaptive value of musculature protection against the compressive force of gravity on our spines, may explain our responsiveness to a load on the head.’

“If your spine is inflexibly stiff at 30, you are old.

If it is completely flexible at 60, you are young.

You are as old as your spine.”

Healthy posture contributes to being able to live pain-free

Our posture has a huge impact on our health and having a forward head posture can negatively affect many bodily functions including blood pressure, gastrointestinal problems, hormone production and can diminish lung capacity by as much as 30%. Over time poor posture results in pain, muscle aches, tension and headache and can lead to long-term complications such as osteoarthritis and degenerative joint disease through the accelerated ageing of intervertebral joints. Ideal posture is the position from which the musculoskeletal system functions most efficiently and there is a direct relationship between chronic poor posture and chronic pain conditions, partly because of how an unnatutural forward head posture pulls the spine out of alignment and increases strain on the muscles, ligaments, fascia and bones of the spinal column.

The familiar modern, sedentary posture results in our head being held in a forward position which stresses the lower cervical vertebrae and one study notes that ‘for every inch (2.5cm) of Forward Head Posture, it can increase the weight of the head on the spine by an additional 10 pounds (13kg)’.

Dr. Roger Sperry, a neuropsychologist, neurobiologist and Nobel laureate, stated that “better than 90% of the energy output of the brain is used in relating the physical body in its gravitational field. The more mechanically distorted a person is, the less energy available for thinking, metabolism and healing.”

Head-loading is impossible to perform correctly without achieving an ideal head and neck alignment. Alongside the development of the relevant stabilising muscles that develop, so too does a particular gait pattern which is a third more efficient than our normal walking gait.

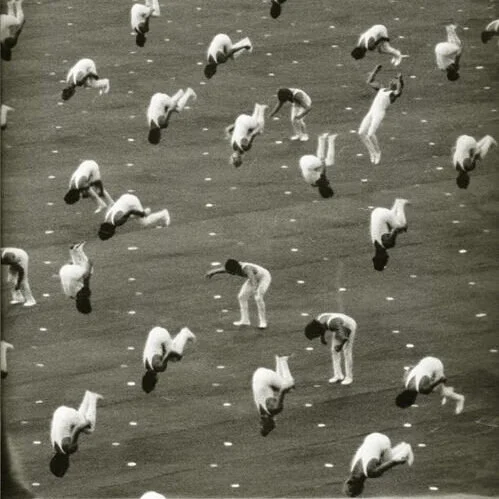

Carrying a load on the head seems to trigger an energy-saving mechanism in the gait. Research carried out by Giovanni Cavagna measured the forces exerted through the feet of women walking normally and head-loading. Despite there being no visible change in the way the women walked, the moment when our leg is lifted before being placed on the ground, shortened substantially. This efficiency of movement enables them to convert more of their potential energy into forward motion rather than muscle heat.

Studies haven’t agreed upon the ideal weight and frequency of head-loading; too much and there is likely to be damage to the cervical spine and too little and we may end up with forward head postures that also damage our cervical spine. Somewhere lies the sweet spot; the same goes for the balance between the dangerous repetitive loading of the ‘developing’ world and the dangerous sedentary behaviour of the ‘developed’ world.

How to head-load

With the incredible array of workouts and methods on the market today, very few - if any - include any form of weighted head-loading. It’s even gone under the radar of the functional fitness crowd, who love their core and stabilising routines. 2021 shall be the year this universal skill is re-discovered for its therapeutics and aesthetic value (and no doubt someone will monetise it).

Here at Movementum we prefer to focus on whole-body movements that our ancestors used in their daily life instead of creating endless exercise routines targeted on fixing a particular issue. Exercise itself is a symptom of domestication, so we are excited to add this new movement into our life and our aim is to be able to carry our weekly shopping home using this method. However, we are starting slowly because we don’t want to damage our cervical spine by over-loading and over-training, so we’ll start light in order to strengthen the right muscles and build up spinal bone density. I’ve read some blogs which have stated rather bluntly that head-loading only works well if you’ve been practicing it for many years; this is true, but can be applied to all skills in life - we generally get better the more we do something.

Research has shown that people can carry loads of up to 20% of their own body weight without expending any extra energy beyond what they’d use by walking; any increase in the load does indicate that metabolic costs seem to increase proportionally with load weight. Initially, head-carrying will require more energy than using a rucksack.

To begin with place a bag of rice in a tea towel (you can start at 500g or 1kg depending on your fitness and injury history) and knot it closed. Place on your head and walk around. You can sit at your desk, watch TV or put a timer on and wander around your house for ten minutes. Build up weight and time progressively.

Give it a go and let me know your experience in the comments below.

REFERENCES

Lloyd, Ray & Parr, B & Davies, Simeon & Cooke, Carlton. (2009). Subjective perceptions of load carriage on the head and back in Xhosa women. Applied ergonomics. 41. 522-9. 10.1016/j.apergo.2009.11.001

The mechanics of head-supported load carriage by Nepalese porters, G. J. Bastien, P. A. Willems, B. Schepens, N. C. Heglund, Journal of Experimental Biology 2016 219: 3626-3634; doi: 10.1242/jeb.143875

Liu, Wentai & Chae, Moo Sung & Yang, Zhi & Kim, Hyunchul. (2009). Design of Advanced Neuroscience Platform. Conference proceedings : ... Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Conference. 2009. 5535-8. 10.1109/IEMBS.2009.5333190.

Grabowski A, Farley CT, Kram R. Independent metabolic costs of supporting body weight and accelerating body mass during walking. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2005 Feb;98(2):579-83. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00734.2004. PMID: 15649878.

Yvon Chouinard: Ode to Tumplines

The Science of Carrying Things on Your Head

Why It’s Better to Carry Weight on Your Head

The Basket Men of Covent Garden

Energetics of Load Carrying in Nepalese Porters, Guillaume J. Bastien, Bénédicte Schepens, Patrick A. Willems, Norman C. Heglund, Science 17 Jun 2005 : 1755

Perrin Roger. Rééducation vertébrale, Principes Techniques. Librairie Le François. Paris. 1979.

Can One Carry Heavy Things on Their Head Pain-Free? A Review of Geere 2010

Teaching My 95-Year-Old Lithuanian Mom the Gokhale Method

Heglund NC, Willems PA, Penta M, Cavagna GA. Energy-saving gait mechanics with head-supported loads. Nature. 1995 May 4;375(6526):52-4. doi: 10.1038/375052a0. PMID: 7723841

Maloiy GM, Heglund NC, Prager LM, Cavagna GA, Taylor CR. Energetic cost of carrying loads: have African women discovered an economic way? Nature. 1986 Feb 20-26;319(6055):668-9. doi: 10.1038/319668a0. PMID: 3951538

A comparison of the physiological consequences of head-loading and back-loading for African and European women R. Lloyd, B. Parr, S. Davies, T. Partridge and C. Cooke

Sperry, R. W. (1988) Roger Sperry’s brain research. Bulletin of The Theosophy Science Study Group 26(3-4), 27-28. Nerve Connections. Quart. Rev. Biol. 46, 198

O'Keefe JH, Vogel R, Lavie CJ, Cordain L. Achieving hunter-gatherer fitness in the 21(st) century: back to the future. Am J Med. 2010 Dec;123(12):1082-6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.04.026. Epub 2010 Sep 16. PMID: 20843503

Cavagna GA, Legramandi MA. The phase shift between potential and kinetic energy in human walking. J Exp Biol. 2020 Nov 12;223(Pt 21):jeb232645. doi: 10.1242/jeb.232645. PMID: 33037111.

On Walking, Carrying Loads, and Efficiency

Dave BR, Krishnan A, Rai RR, Degulmadi D, Mayi S. The Effect of Head Loading on Cervical Spine in Manual Laborers. Asian Spine J. 2021 Feb;15(1):17-22. doi: 10.31616/asj.2019.0221. Epub 2020 Mar 30. PMID: 32213796; PMCID: PMC7904483.

What are the most common misconceptions about furniture free? Well these are my top three!