The Touch-Deprived New Normal

Franklin D. Roosevelt said, ‘the only thing we have to fear is fear itself’ and this is as relevant now as it was when he uttered those words in 1932.

We’ve stayed relatively quiet as we’ve watched this new world being erected around us. However, it is time to speak out; we do not want to live in a world where we fear each other and are afraid of connection. The future being discussed on TV and by the legacy media is one in which physical touch is minimised or eliminated so we can live ‘safely’ (a relative term).

‘With the coronavirus pandemic making human touch a potentially lethal act since the virus can be transmitted with skin contact, handshaking has suddenly become socially unacceptable.’ - USA TODAY, BBC, The Independent etc etc.

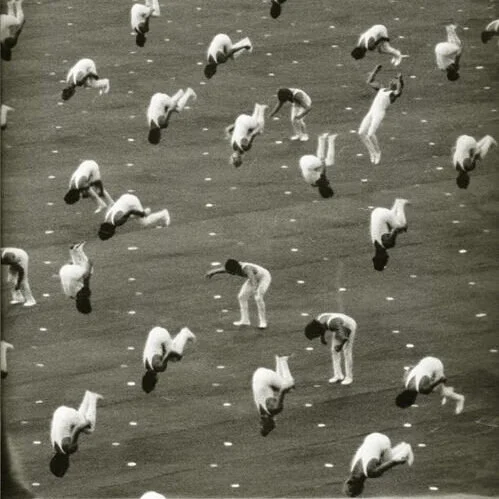

Suddenly, in an already chronically touch-deprived society, we’re facing a complete break with any touch, be it a handshake or a supporting arm on the shoulder. This is conditioning us to associate touch with being unsafe, deadly and negative.

Human touch is a need not a choice. We are wired to be touched from birth until death and positive touch activates a big bundle of nerves in our body that improves our immune system, regulates digestion and helps us sleep well. Being touch-starved - also known as skin hunger or touch deprivation - occurs when a person experiences little to no touch from other living things.

There is plenty of research showing the myriad of reasons why touch is so important and the effects that happen physically, mentally and developmentally if we are don’t get it. The current conditioning for a future with little or no touch will yield bitter fruit; we need to widen our perspective and take many things into account before erecting a ‘new normal’ where we are deprived of touch and we fear it. The best way to combat fear is through understanding and I wanted to share some studies and observations that show how important touch is to our wellbeing.

A study of 404 healthy adults intentionally exposed them to a common cold virus and monitored them in quarantine to assess their infection and signs of illness. The results showed that perceived social support reduced the risk of infection associated with experiencing conflicts. Hugs were responsible for one-third of the protective effect of social support. Among infected participants, greater perceived social support and more frequent hugs both resulted in less severe illness symptoms.

Growing up in conditions that limit or remove touch can have profound implications on a child’s development and lack of touch can also be considered a form of neglect.

The Effects of Isolation

Children

Isolation is severely detrimental to a child’s social development and many experiments and research are clear about the catastrophic effects sensory and social deprivation at certain critical periods in early childhood can have on children’s subsequent development. It is necessary for babies and children to be around loving and caring caregivers to enable proper social development and the younger the child is when they experience social isolation, the more pronounced the effect will be.

Children who are isolated during the early years of their lives are less playful than those who are socialised, often develop disturbing behaviour and have trouble connecting with their peers. They may be physically healthy, yet develop disturbed social behaviour as a result of prolonged lack of contact with others.

In the thirteenth century, the German King Frederick II was known for being fascinated by the natural sciences and conducted many different experiments including nailing prisoners into wooden casks to see whether the human soul could be seen at the moment of death. He was fascinated by the origins of language and devised an experiment to prove what the original, default language was. Frederick assigned nurses to care for babies and had strict instructions on how to raise them. This meant there was to be no interaction with them, they were to be bathed and fed only, and never spoken to. The children, deprived of all forms of maternal care, affection and social interaction died.

Fast forward to the nineteenth and early twentieth century and science exerted a profound influence over the behaviour of parents to their children, having superseded religion as the place to go for answering questions and solving dilemmas; this gave rise to a whole industry of parenting experts using behaviorism, psychology and the scientific method as justification for their advice. This developed into a rigid, detached form of parenting which advocated withholding affection, ignoring cries and minimal physical contact with infants. Failure to do this would result in the child growing up spoiled and, if they were a boy, they may become ‘un-manly’. If children were admitted to hospital, their parents were not permitted to stay with them and they may be in the hospital for significant amounts of time alone or an occasional weekly half an hour visit. In 1928 behaviourist John Broadus Watson wrote the famous ‘Psychological Care of Infant and Child’ in which he emphasised these principles, saying “it is a serious question in my mind whether there should be individual homes for children -- or even whether children should know their own parents. There are undoubtedly much more scientific ways of bringing up children which will probably mean finer and happier children”.

In the 1940s, René Spitz followed two groups of children for several years from the time they were born and his work was one of the first to highlight how social interactions with other humans are essential for children’s development. The first group were babies raised in a nursery prison where their mother's were incarcerated and the second group were raised in an orphanage. The first group of babies were allowed daily contact with their mothers, prison staff and other children and the second group were alone in their cribs where a single nurse cared for seven children. By 4 months old, both groups state of development was similar yet by the time they were a year old, the motor and intellectual performance of those reared in the orphanage lagged badly behind those reared in the prison nursery. By the ages of 2 and 3, the children raised in prison walked and talked confidently and showed development comparable to that of children raised in normal family settings. But of the 26 children reared in the orphanage, only 2 could walk and most could only manage a few words. The children raised in the orphanage were also more subject to infections as well as being less playful and curious.

In the 1960s, Harry Harlow developed an experimental model that took previous studies even further and showed beyond any doubt that in monkeys as in humans, there is a critical period for social development. Harlow took newborn monkeys and raised them for 3, 6, or 12 months in complete isolation from any other monkeys, including their mothers. When put back with other monkeys, the monkeys who had been isolated remained physically healthy, but their social behaviour was completely disturbed. They would huddle in the corners of their cages and rock back and forth; they did not interact with other monkeys, or play, or show any sex drive. But when other monkeys were isolated for periods of comparable length later in life, it had practically no effect on their behaviour.

In 2021, the municipality of the Peel region of Canada issued guidelines to parents instructing them to keep any children who have been sent home because a classmate has tested positive for Covid-19 isolated in a separate room from all other family members for 14 days. The severe guidelines, which apply even to small children who are dismissed from child care, have been criticised by experts as harmful and not supported by science.

Zoo Animals

In humans, deprivation can trigger psychiatric issues, including depression, anxiety, mood disorders or post-traumatic stress disorder and the detrimental effects of social deprivation and separation have been widely documented in many species and are known to cause behavioural and physiological indications of stress. Recent research finds that large mammals suffer brain damage due to the ill-effects of captivity and this negative impact is particularly applicable to cetaceans (dolphins and whales) and elephants.

Social living is a major component of health and a major source of complex mental stimulation for many animals. It confers many benefits beyond avoiding predation and finding food. Chronic frustration and boredom arise when animals live in enclosures that restrict or prevent normal behaviour. Captivity disempowers animals and they have no control over their environment; a situation which fosters learned helplessness. This disrupts the delicate balance of serotonin, a neurotransmitter that stabilises mood and the amygdala, which processes emotions, is impacted. Prolonged stress elevates stress hormones with memory functions inhibited due to the negative effects on the hippocampus.

Behaviours exclusively seen in captivity are caused by an absence of some natural necessity: social, nutritional, environmental, nutritional, physical. Self-directed behaviours such as feather-plucking, rocking, sucking and crouching in abnormal postures can be observed in a wide range of species such as rodents, primates and birds. These actions are often the result of anxiety and stress caused by a lack (or excessive amount) of being around the same species.

Prisoners

Solitary confinement causes long-lasting harm and isolation causes severe and permanent damage and has led the United Nations to consider it to be classed as torture when used for longer than 15 consecutive days. The Mandela Rules, updated in 2015, are a revised minimum standard of UN rules that defines solitary confinement as ‘the confinement of prisoners for 22 hours or more a day without meaningful human contact.’

The deprivation of meaningful social contact is extremely harmful and there are many studies demonstrating the myriad of ways it wreaks havoc on the human mind and body. Social pain affects the brain in the same way as physical pain, and can actually cause more suffering because of humans’ ability to relive social pain months or even years later. It’s possible for people placed in solitary confinement to develop mental health issues due to the effects of isolation and despite people in solitary confinement comprising only 6% to 8% of the total prison population, they account for approximately half of those who die by suicide.

“The severe and often irreparable psychological and physical consequences of solitary confinement and social exclusion are well documented and can range from progressively severe forms of anxiety, stress, and depression to cognitive impairment and suicidal tendencies...This deliberate infliction of severe mental pain or suffering may well amount to psychological torture..Inflicting solitary confinement on those with mental or physical disabilities is prohibited under international law. Even if permitted by domestic law, prolonged or indefinite solitary confinement cannot be regarded as a ‘lawful sanction’ under the Mandela Rules.”

- Mr. Nils Melzer, Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, is part of what is known as the Special Procedures of the Human Rights Council.

We can’t be alone, together

The campaign to end loneliness highlights the mental and physical effects of social isolation. A study showed that loneliness and social isolation were associated with a 29% increase in coronary heart disease and a 32% rise in the risk of stroke; we won’t know the long-term effects of the current Lockdown policy for a long time, but previous research has highlighted many potential consequences.

Loneliness and physical health

Loneliness increases the likelihood of mortality by 26%[1]

The effect of loneliness and isolation on mortality is comparable to the impact of well-known risk factors such as obesity, and has a similar influence as cigarette smoking[2]

Loneliness is associated with an increased risk of developing coronary heart disease and stroke[3]

Loneliness increases the risk of high blood pressure[4]

Social isolation and loneliness are risk factors for the progression of frailty[5]

Loneliness and mental health

Loneliness puts individuals at greater risk of cognitive decline and dementia[6]

Lonely individuals are more prone to depression[7]

Loneliness and low social interaction are predictive of suicide in older age[8]

Loneliness and isolation are associated with poorer cognitive function among older adults[9]

Pathways to loneliness

The pathways to explain how loneliness affects health are difficult to demonstrate. Three main pathways have been suggested: behavioural, psychological and physiological.

Social isolation and loneliness adversely influence activities of daily living that include functional status (individual’s ability to perform normal daily activities required to meet basic needs, fulfil usual roles, and maintain health and well-being) among older adults[10]

Have a direct influence on health related physiology such as blood pressure and reduced immune functioning[11]

People reporting loneliness have poorer sleep quality[12]

Both social isolation and loneliness were associated with a greater risk of being inactive, smoking, as well as reporting multiple health-risk behaviours including physical inactivity and smoking[13]

Loneliness is associated with lower self-esteem and limited use of active coping mechanisms[14]

The UK Health Secretary Matt Hancock (who, it's noted on his Wiki page, has a degree in Philosophy, Politics and Economics and not any relevant health qualifications) suggests there be no hugging until a coronavirus vaccine or treatment is found. This is rather convenient for him, as he serves as the ‘person with significant control’ for Porton Biopharma ltd, which according to its website, was ‘established in 2015, to commercialise the pharmaceutical development and manufacturing capabilities at the Porton Down site in Wiltshire that were previously within Public Health England. Our mission is to protect patients’ health through the quality-assured development and production of biopharmaceuticals.’

Throughout this Governmental King Canute-like response to a virus, one thing has come to our attention and that is the absence of discussion about quality of life. It is too simplistic to frame these kinds of arguments in binary terms - you’re either pro-life (an advocate of lockdown) or pro-economy (a lockdown ‘denier’). The continuing lack of nuance in the wider debate highlights other issues that aren’t relevant to this blog post, but what does need to be asked is ‘what kind of life?’ A life normalised to fear and recoil from human touch has long-term implications for the individual and for society. Whether we like it or not we are mammals and encoded within us are certain needs. Yes, as humans we are incredibly adaptable but we deny the expression of our biological reality at our peril.

REFERENCES

Cohen, S., Janicki-Deverts, D., Turner, R. B., & Doyle, W. J. (2015). Does hugging provide stress-buffering social support? A study of susceptibility to upper respiratory infection and illness. Psychological science, 26(2), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614559284

René A. Spitz (1946) Hospitalism, The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 2:1, 113-117, DOI: 10.1080/00797308.1946.11823540

American adolescents touch each other less and are more aggressive toward their peers as compared with french adolescents.." the free library. 1999 libra publishers,inc. 14 may. 2020 https://www.thefreelibrary.com

Valtorta NK, Kanaan M, Gilbody S, Ronzi S, Hanratty B. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Vol. 102, Heart. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and British Cardiovascular Society; 2016. p. 1009–16. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27091846. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

1] Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T.B., Baker, M., Harris, T. and Stephenson, D., 2015. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspectives on psychological science, 10(2), pp.227-237

[2] Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T.B. and Layton, J.B., 2010. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS medicine, 7(7), p.e1000316.

[3] Valtorta, N.K., Kanaan, M., Gilbody, S., Ronzi, S. and Hanratty, B., 2016. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart, 102(13), pp.1009-1016.

[4] Hawkley, L.C., Thisted, R.A., Masi, C.M. and Cacioppo, J.T., 2010. Loneliness predicts increased blood pressure: 5-year cross-lagged analyses in middle-aged and older adults. Psychology and aging, 25(1), p.132.

[5] Social isolation and loneliness as risk factors for the progress ion of frailty: the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Gale C, Westbury L, Cooper C, the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, Age and Ageing, Volume 47, Issue 3, 1 May 2018, Pages 392–397

[6] Global Council on Brain Health. (2017). The brain and social connectedness: GCBH recommendations on social engagement and brain health. Retrieved from www.GlobalCouncilOnBrainHealth.org.

[7] Cacioppo, J.T. and Cacioppo, S., 2014. Older adults reporting social isolation or loneliness show poorer cognitive function 4 years later. Evidence-based nursing, 17(2), pp.59-60.

[8] O’Connell, H., Chin, A.V., Cunningham, C. and Lawlor, B.A., 2004. Recent developments: suicide in older people. Bmj, 329(7471), pp.895-899.

[9] Cacioppo, J.T. and Cacioppo, S., 2014. Older adults reporting social isolation or loneliness show poorer cognitive function 4 years later. Evidence-based nursing, 17(2), pp.59-60.

[10] Shankar, Aparna, et al. “Social isolation and loneliness: Prospective associations with functional status in older adults.” Health psychology 36.2 (2017): 179.

[11] Holt-Lunstad, Julianne. “The potential public health relevance of social isolation and loneliness: Prevalence, epidemiology, and risk factors.” Public Policy & Aging Report 27.4 (2017): 127-130.

[12] Cacioppo, J.T., Hawkley, L.C., Crawford, L.E., Ernst, J.M., Burleson, M.H., Kowalewski, R.B., Malarkey, W.B., Van Cauter, E. and Berntson, G.G., 2002. Loneliness and health: Potential mechanisms. Psychosomatic medicine, 64(3), pp.407-417.

[13] Valtorta, N.K., Kanaan, M., Gilbody, S., Ronzi, S. and Hanratty, B., 2016. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart, 102(13), pp.1009-1016.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Dreyer K, Stevenson A, Fisher R, Deeny SR. The association between living alone and health care utilisation in older adults: a retrospective cohort study of electronic health records from a London general practice. BMC Geriatrics 2018;18:269 Available at: https://bmcgeriatr.biomed-central.com/articles/10.1186/s12877-018-0939-45.

[16]Ibid.

[17] Hanratty B, Stowl D, Collingridge Moore D, Valtora NK. Loneliness as a risk factor for care home admission in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Age and Ageing 2018;47(6):896–900

[18]Hanratty B, Stowl D, Collingridge Moore D, Valtora NK. Loneliness as a risk factor for care home admission in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Age and Ageing 2018;47(6):896–900

The science of solitary: expanding the harmfulness narrative

United States: prolonged solitary confinement amounts to psychological torture, says UN expert

The Experience of Touch: Research Points to a Critical Role

Ardiel EL, Rankin CH. The importance of touch in development. Paediatr Child Health. 2010;15(3):153-156. doi:10.1093/pch/15.3.153

Stone, L. Joseph. “A Critique of Studies of Infant Isolation.” Child Development, vol. 25, no. 1, 1954, pp. 9–20. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1126148. Accessed 13 Feb. 2021.

Psychogenic Disease in Infancy

Grief, A Peril in Infancy (Spitz and Wolf, The Research Project, 1947)

Van der Horst, Frank & van der Veer, René. (2008). Loneliness in Infancy: Harry Harlow, John Bowlby and Issues of Separation. Integrative psychological & behavioral science. 42. 325-35. 10.1007/s12124-008-9071-x.

Love at Goon Park: Harry Harlow and the Science of Affection

Emperor Frankenstein: The Truth Behind Frederick II of Sicily’s Sadistic Science Experiments

Jeremy Jolley, Linda Shields, The Evolution of Family-Centered Care, Journal of Pediatric Nursing, Volume 24, Issue 2, 2009, Pages 164-170, ISSN 0882-5963, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2008.03.010.

John Broadus Watson - ‘Psychological Care of Infant and Child’

Peel Region Guidelines for self-isolating children

Experts call Peel guidelines to place children in solitary quarantine ‘cruel punishment’

![Screenshot_2020-07-15 Jay Dyer’s Instagram photo “I’m told this is what elementary school is like now is this real If so, I[...].png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a7989439f07f5f97873172d/1594808660727-FYPR8SIHJPT4UDKR99HZ/Screenshot_2020-07-15+Jay+Dyer%E2%80%99s+Instagram+photo+%E2%80%9CI%E2%80%99m+told+this+is+what+elementary+school+is+like+now+is+this+real+If+so%2C+I%5B...%5D.png)

What are the most common misconceptions about furniture free? Well these are my top three!