Don't Stay Home If You Want To Save Lives

Many of us have been spending a significant amount of time indoors this spring and summer. With the ongoing situation with Covid-19, much has been made of staying safe inside, but little information has come out on the benefits of sunshine and fresh air in keeping healthy.

Sunshine and Vitamin D

Vitamin D is made through a series of biochemical processes that start when the skin is exposed to the sun’s UV rays. Studies show a link between vitamin D supplements and a reduced severity and frequency of colds and upper-respiratory tract infections.

NHS England discusses vitamin D:

‘Most ‘people can make enough vitamin D from being out in the sun daily for short periods with their forearms, hands or lower legs uncovered and without sunscreen from late March or early April to the end of September, especially from 11am to 3pm. It's not known exactly how much time is needed in the sun to make enough vitamin D to meet the body's requirements.

There are a number of factors that can affect how vitamin D is made, such as your skin colour or how much skin you have exposed. People with dark skin, such as those of African, African-Caribbean or south Asian origin, will need to spend longer in the sun to produce the same amount of vitamin D as someone with lighter skin. In the UK, sunlight doesn't contain enough UVB radiation in winter (October to early March) for our skin to be able to make vitamin D. During these months, we rely on getting our vitamin D from food sources (including fortified foods) and supplements.’

In 2017, The BMJ released a systematic review and meta-analysis using data from 25 randomised controlled trials where more than 11,000 participants were given either vitamin D or a placebo. The authors concluded that vitamin D supplementation is safe and protects against acute respiratory tract infection and noted that it was necessary to treat only four people who are deficient in vitamin D to prevent one case of acute infection. Critical care research also documents the important effect of vitamin D on survival in ICU patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Is there a connection between Covid-19 and vitamin D?

Vitamin D deficiency may or may not help to prevent you catching the virus, but it does affect whether you get very ill from it. A recent study in Chicago concluded that it 'argues strongly for a role of vitamin D deficiency in Covid-19 risk and for expanded population-level vitamin D treatment and testing and assessment of the effects of those interventions.'

History of Open Air Treatment

The English physcian John Coakley Lettsom was one of the first advocates of the ‘open-air method’ and, in 1796, founded The Royal Sea Bathing Hospital in Margate, UK which claimed to be the earliest specialist orthopaedic hospital in Britain, if not the world, and was a pioneer in the use of open-air treatment for patients with non-pulmonary tuberculosis.

George Bodington founded the first tuberculosis sanatorium in Sutton Coldfield near Birmingham, England. His treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis was a combination of gentle exercise outdoors, fresh air, a varied nutritious diet and the minimum of medicines.

Florence Nightingale wrote about the importance of sunlight and fresh air in the 1850s in the recovery of hospital patients.

In the mid-19th century a new approach to treating tuberculosis was established in Germany. Patients were treated in the open air until their fever subsided.

In 1884, Edward Livingston Trudeau opened America’s first sanatorium at Saranac Lake in New York State and 1899 a group of Scottish physicians recommended Banchory as the most desirable place in Scotland to build a sanatorium because of the dry sunny climate, the beneficial vapours from the pine trees and over 2.5% ozone in the air.

“It is essential for patients to spend the whole of their time in pure air. In order that they may do this with a maximum of comfort, the buildings have been specially designed. All bedrooms face south, and are heated by steam pipes, lighted by electricity, and fitted with hot and cold water supply; the floors being covered with a material which readily ensures absolute cleanliness. Adjacent to the commodious dining room are the Winter Garden, the writing room, and the library, which contains over 3000 volumes in addition to a wide selection of current papers and magazines. The Technical Equipment includes Laboratory, X-ray Department, Light Room, Throat Room, Dental Room, Examination and Pneumothorax Room”

- Dr David Lawson of Banchory

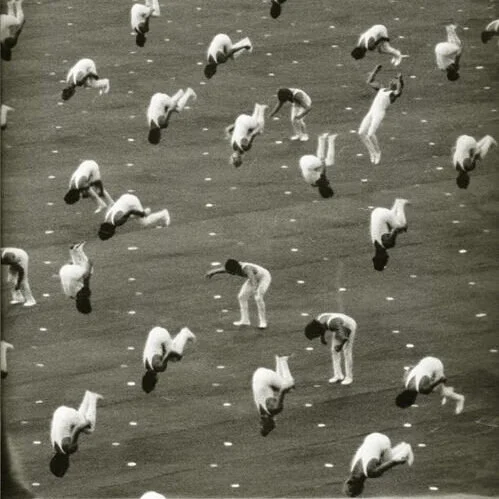

By 1908 there were at least 90 of the ‘Nordrach’ open-air sanatorium in the UK. These were based on the Nordrach-Kolonie in the Black Forest, Germany which was established in 1888 by Otto Walter and this was followed in 1904 by an open-air recovery school for tubercular children in Charlottenburg, a suburb of Berlin. Also at this time there was the open-air school movement which I’ve written about here - Outdoor Classrooms - Time For A Comeback?

Fever Hospitals

In 1929 there were 635 fever hospitals of less than 100 beds in England and Wales. They were often purposely built in the countryside with sunshine and fresh air and contained isolation wards, separate accommodation for different infections, laboratories, operating theatres, convalescent wards and activities for recovering patients.

Staffed by specialists, many remained closed except during epidemic outbreaks where there open-plan designed meant that they could be quickly converted into separated isolation rooms at relatively low cost.

Unlike today, these people recognised the need for a flexible response in times of sickness and urgency and they also understood the madness of receiving and housing infectious and non-infectious patients in the same facilities.

These fever hospitals closed and infectious patients are now sent to the usual district general hospital, where patients with suspected infections mix with non-Covid-19 patients. As one physician wrote, “The utter failure of sound clinical leadership will lead to an absolute explosion of hospital-acquired Covid-19 infection.”

Jonathan Tepper writes how ‘Italian doctors have written that ‘rationalizing and industrializing’ medical care has made infectious diseases worse. They note that in many older hospitals, there was a separate pavilion, with separate entrances and exits which made it possible to prevent contact between patients affected by different illnesses.

Modern hospitals are different. “Having 19 posts directing patients towards 120 consultation rooms mean that every day, if the system works at full efficiency, over 1000 patients wait in line, sit on a bench, enter a room, go back to the secretary, make another appointment, and finally wait for transportation to go home.”

They noted that, “We are now slowly realizing that this ‘super-efficient’, factory-like, program is incompatible with the periodic occurrence of epidemics.”’

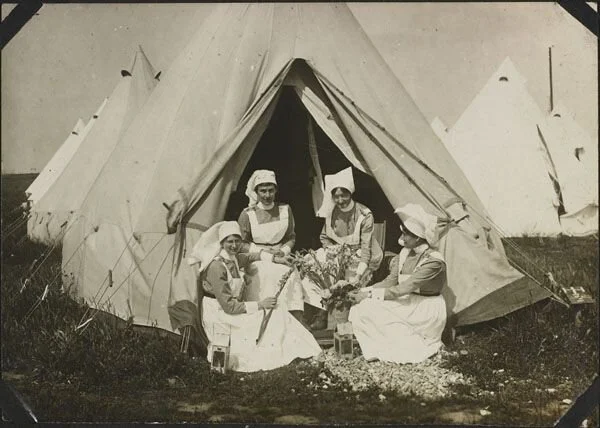

The First World War

Hospitals were often housed in tents during the First World War, including wards and operating theatres set up immediately behind the front lines. At the beginning of the War, Colonel Joseph Griffiths, a surgeon at Addenbrooke’s Hospital, led plans to build a large open-air field hospital in Cambridge, UK to be called the First Eastern General Hospital.

6,600 patients had passed through the hospital, with a death rate of 4.6 per 1000. Of the 60 patients with pneumonia that were treated, 95% of them recovered. Critics ascribed the low mortality at the hospital to the absence of ‘bad cases,’ however this was disputed by A. E. Shipley who stated that entire convoys coming straight from the trenches could easily be considered as ‘bad cases’. The results showed that people treated outside had a better recovery rate than people treated indoors, particularly for those with pneumonia.

In the treatment of all gunshot wounds where the septic processes are raging, and the temperature varies through several degrees, an immense advantage will accrue from placing patients out of doors. While in France I developed a great affection for the tented hospitals. There is great movement of air, warmth and comfort; when a sunny day comes the side of the tent may be lifted and the patient enjoys the advantage of open-air treatment.”

- Lieutenant Colonel Sir Berkeley Moynihan, military surgeon, 1916

Spanish Flu Pandemic

Over 100 years ago, while an influenza pandemic spread worldwide, ‘open air’ treatment were effective in saving many lives thanks to a combination of fresh air, sunlight, scrupulous standards of hygiene, and reusable face masks which were credited with substantially reducing deaths among patients and infections among medical staff. With the success of the open-air treatments used during the First World War, medical personnel soon discovered that flu patients treated outdoors recovered better than indoor flu patients. They didn’t know why the open-air treatment worked, but subsequent research suggests that putting infected patients out in the sun may help because it inactivates the influenza virus.

Dr. Richard Hobday writes:

‘When the influenza pandemic reached the East coast of the United States in 1918, the city of Boston was particularly badly hit. So the State Guard set up an emergency hospital. They took in the worst cases among sailors on ships in Boston harbour. The hospital’s medical officer had noticed the most seriously ill sailors had been in badly-ventilated spaces. So he gave them as much fresh air as possible by putting them in tents. And in good weather they were taken out of their tents and put in the sun. At this time, it was common practice to put sick soldiers outdoors. Open-air therapy, as it was known, was widely used on casualties from the Western Front. And it became the treatment of choice for another common and often deadly respiratory infection of the time; tuberculosis. Patients were put outside in their beds to breathe fresh outdoor air. Or they were nursed in cross-ventilated wards with the windows open day and night. The open-air regimen remained popular until antibiotics replaced it in the 1950s.’

The pandemic arrived in Boston, Massachusetts, early in September and by October 1919 it had claimed 4000 lives out of a total population of less than 800,000. At the peak of the outbreak, more than 25% of patients at an emergency hospital in Philadelphia died each night, many without seeing a nurse or doctor. One general hospital had 76 cases which resulted in 17 nurses falling ill and 20 patients died within 3 days of submission. The Camp Brooks tent hospital, by contrast, reduced the fatality of thier cases from 40% to about 13%.

‘The efficacy of open air treatment has been absolutely proven, and one has only to try it to discover its value.’

- Surgeon General of the Massachusetts State Guard

Dr. Richard Hobday described conditions at the hospital and posits some reasons why open-air treatment was successful:

‘The treatment at Camp Brooks Hospital took place outdoors, with ‘a maximum of sunshine and of fresh air day and night.’ The medical officer in charge, Major Thomas F. Harrington, had studied the history of his patients and found that the worst cases of pneumonia came from the parts of ships that were most badly ventilated. In good weather, patients were taken out of their tents and put in the open. They were kept warm in their beds at night with hot-water bottles and extra blankets and were fed every few hours throughout the course of the fever. Anyone in contact with them had to wear an improvised facemask, which comprised five layers of gauze on a wire frame covering the nose and mouth. The frame was made out of an ordinary gravy strainer, shaped to fit the face of the wearer and to prevent the gauze filter from touching the nostrils or mouth. Nurses and orderlies were instructed to keep their hands away from the outside of the masks as much as possible. A superintendent made sure the masks were replaced every two hours, were properly sterilised, and contained fresh gauze.

Other measures to prevent infection included the wearing of gloves and gowns, including a head covering. Doctors, nurses, and orderlies had to wash their hands in disinfectant after contact with patients and before eating. The use of common drinking cups, towels, and other items was strictly forbidden. Patients’ dishes and utensils were kept separate and put in boiling water after each use. Extensive use was made of mouthwash and gargle, and twice daily, the proprietary silver-based antimicrobial ointment Argyrol was applied to nasal mucous membranes to prevent ear infection.

Putting infected patients out in the sun may have helped because it inactivates the influenza virus. It also kills bacteria that cause lung and other infections in hospitals. During the First World War, military surgeons routinely used sunlight to heal infected wounds. They knew it was a disinfectant. What they didn’t know is that one advantage of placing patients outside in the sun is they can synthesize vitamin D in their skin if sunlight is strong enough. This was not discovered until the 1920s. Low vitamin D levels are now linked to respiratory infections and may increase susceptibility to influenza. Also, our body’s biological rhythms appear to influence how we resist infections. New research suggests they can alter our inflammatory response to the flu virus. As with vitamin D, at the time of the 1918 pandemic, the important part played by sunlight in synchronizing these rhythms was not known.”’

Rejecting the lessons of the past : Covid-19 Government Regulations

As you’re reading this, there may be people who haven’t left their houses since they were compelled to ‘stay home and save lives’. They took that literally, despite evidence from the last 100 years showing how beneficial sunlight and fresh air are for health. The UK Government claims that Covid-19 can be spread when people spend more than 15 minutes within 2 metres of an infected person; quite why this warrants a near complete closure of all public parks and nature reserves has never been made clear.

Other countries have educated their people and relied on them using their own common sense; Japan is a densely populated country of 126 million people with a land mass of 145,897 square miles which has had 903 Covid-19 related deaths with no lockdown enforced. Contrast this with the UK which has an estimated total land area of 94,600 square miles, is home to 66 million people and has had 39,904 Covid-19 related deaths.

In France outdoor exercise was only permitted for one hour maximum once a day, alone and within 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) of home. Bikes were banned and anyone going outside had to print out a certificate at home declaring their reason for leaving the house, which the police checked enthusiastically. Those who violated the lockdown faced fines of between €135 to €3,700 as well as up to six months in prison for multiple violations. Eventually all outdoor sports, including jogging, were banned in Paris between 10 a.m. and 7 p.m.

In America State and National parks were closed along with beaches, further limiting access for people to fresh air and sunshine. For all of those people with gardens, it’s worth bearing in mind there are an awful lot of people who live in apartments with no communal outside area and no access to sunlight and fresh air at a time when it was most needed.

On top of cooping everyone up inside, there’s the added problem that indoor air quality is notoriously poor, containing high levels of VOCs, allergens and pollutants and exacerbated by the toxic cleaning products a lot of people have taken to using. For a more detailed discussion of this, please read my blog post Why Office Air Is Making You Sick.

Hospital-acquired Covid-19

Marita Edwards, a retired cleaner and keen golfer, went to Newport’s Royal Gwent hospital for a routine gallbladder operation on 28 February. The otherwise fit 80-year-old then caught an infection in hospital that she and her family were initially told was pneumonia. Almost 3 weeks after arriving at the hospital, she tested positive for Covid-19 and died the following day. The first official Covid-19 death was a result of hospital-acquired Covid-19.

Hospital-acquired infections are known as nosocomial infections and spread predominantly within hospitals (and can thus pass into care homes because the elderly visit hospitals a lot), the most famous of which is probably MRSA.

NHS officials have admitted that there has been a significant problem of inpatients catching Covid-19 from staff or other patients at hospitals around the country with up to 1 in 5 Covid-19 patients in hospital catching the virus whilst being treated for something else. Evidence is emerging that the spread of the disease in both hospitals and care homes may be a critical factor in its morbidity and virulence. This was illustrated in the SAGE meeting minutes on March 20th, which referenced the idea that Covid-19 may be a nosocomial disease:

If the current ICU demand is being driven largely by nosocomial transmission and increased transmission to vulnerable patients and this process is separate from transmission in the general population then it will not be influenced in the short-term by current measures.

Nightingale Hospitals

The NHS Nightingale Hospitals are seven critical care temporary hospitals set up England as a response to the Covid-19 virus. The first patients were admitted in early April, with the aim of the 4,000-bed capacity hospitals being to alleviate the pressure on the city as the virus took hold. According to The Guardian, NHS Nightingale London has remained largely empty, treating 51 patients in its first three weeks with 50 patients in need of ‘life and death’ treatment being turned away due to staff shortages. In early May Nightingale London was put on standby and the patients transferred elsewhere. From the images shown, it appears that these hospitals lack access to natural light and ventilation and there would likely be a high amount of off-gassing from the materials used in their construction, including VOCs, which are not going to be healthy for people in hospital for a respiratory disease.

Health commissioners and providers have not yet disclosed how much it is costing to build and then maintain the running of these temporary hospitals; all that has been confirmed by NHS England is it is a 'nationally funded' project, and that some of the information is 'commercially confidential'. Assurances have been made that what isn't will be in the public domain in 'due course', but no time frame has been provided.

There are many lessons to be learned from treating patients in both World War 1 and the subsequent Spanish Flu Pandemic provide a lot of evidence that simple measures can yield incredibly effective results. The Camp Brooks Open Air Hospital could serve as a useful model in treating pandemics, incorporating the combination of high levels of natural ventilation and fresh air, sunlight, high standards of hygiene and re-usable face masks.

Not only are these methods cost-effective but they are also environmentally friendly as well. Pharmaceutical drugs cannot replace every other method of disease control and it has unwise to not incorporate these ideas into pandemic preparation plans. There has been ample time for research and testing of these methods, but we can see from the last few months there has been little joined up thinking. Vaccines and track-and-trace apps will never be an effective substitute for healthy habits and lifestyle.

Conclusion

There is ample research and data to support the idea that being outdoors decreases the chances of developing respiratory tract infections as well as flu. This information alone should be used to encouraged people to spend time outside every day and help them understand the connection between vitamin D and health.

During the First World War and the Spanish Flu, severely ill patients nursed outdoors recovered better than those treated indoors. Since then there has been a lot of research showing the benefits of being outside as both a prevention for illness and for recovery. In the 1960s scientists in biodefense research found outdoor air to be far more lethal to viruses than indoor air and further studies have shown how rooms exposed to daylight have fewer germs than dark rooms with no natural daylight. Being outdoors reduces the survival and infectivity of pathogens alongside the UV rays acting as both as disinfectants and being synthesised into the body vitamin D.

Following the 2003 SARS outbreak, case studies indicated that natural cross-ventilation is an effective way of controlling SARS infection in hospitals and that germicidal properties could be fully retained in enclosures if ventilation rates were high enough. Typical window glass filters out most UV light, however evening opening windows can help as outdoor air reduces the survival and infectivity of pathogens.

Every years this lack of sun-induced vitamin D in the winter and early spring leads to epidemic acute respiratory infections (and this probably includes viruses like Covid-19). Being confined indoors with reduced sun exposure - especially if you are elderly, obese or dark skinned - will result in a vitamin D deficiency and increase susceptibility to illness and infection. This is reflected in the information coming out of New York City, where early data from 100 NYC hospitals showed that 66% of new Covid-19 cases were people who were ‘sheltering-in-place’ at home.

Misunderstanding the transmission vector of the virus has led to a misdiagnosis of the crisis. As a result, policymakers have offered extreme solutions that do not solve the problem and impose unacceptable costs on society. Instead of focussing almost entirely on cures developed by for-profit pharmaceutical companies, a virus with a 99.76% survival rate can be successfully managed with a model such as Camp Brooks in 1919, using a combination of fresh air, sunlight, and a ‘high standard of personal and environmental hygiene’.

REFERENCES

Up to 20% of hospital patients with Covid-19 caught it at hospital

Lanham-New SA, Webb AR, Cashman KD, et al. Vitamin D and SARS-CoV-2 virus/COVID-19 disease. BMJ Nutrition, Prevention & Health 2020;0. doi:10.1136/bmjnph-2020-000089

Hobday RA, Cason JW. The open-air treatment of pandemic influenza. Am J Public Health. 2009;99 Suppl 2 (Suppl 2):S236‐S242. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2008.134627

Coronavirus (COVID-19): What is social distancing?

May KP, Druett HA. A micro-thread technique for studying the viability of microbes in a simulated airborne state. J Gen Micro-biol 1968;51:353e66. Doi: 10.1099/00221287–51–3–353.

Association of Vitamin D Deficiency and Treatment with COVID-19 Incidence

Spread of covid-19 in hospitals causing national ‘concern’

Cost of building and running Exeter's new Nightingale hospital is kept under wraps

Dancer RCA, Parekh D, Lax S, et al Vitamin D deficiency contributes directly to the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) Thorax 2015;70:617-624.

Martineau AR, Jolliffe DA, Hooper RL, et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory tract infections: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ. 2017;356:i6583. Published 2017 Feb 15. doi:10.1136/bmj.i6583

Nurse shortage causes Nightingale hospital to turn away patients

Cannell, John & Vieth, Reinhold & Umhau, John & Holick, Michael & Grant, William & Madronich, Sasha & Garland, C.F. & Giovannucci, E. (2007). Epidemic influenza and Vitamin D. Epidemiology and infection. 134. 1129-40. 10.1017/S0950268806007175.

Schuit M, Gardner S, Wood S et al. The influence of simulated sunlight on the inactivation of influenza virus in aerosols. J Infect Dis 2020 Jan 14;221(3):372–378. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz582.

Hobday RA. Sunlight therapy and solar architecture. Med Hist 1997 Oct;41(4):455–72. doi:10.1017/s0025727300063043.

Gruber-Bzura BM. Vitamin D and influenza-prevention or therapy? Int J Mol Sci 2018 Aug 16;19(8). pii: E2419. doi: 10.3390/ijms19082419

Ground Zero: When the Cure is Worse than the Disease

Offline: COVID-19 and the NHS—“a national scandal”

SAGE Meeting 18, 23 March 2020 SPI-M-O: Consensus view on COVID-1

How to get vitamin D from sunlight

Grandma Was Right: Sunshine Helps Kill Germs Indoors

The open-air factor and infection control

Flu is 'almost wiped out' and at lowest level in 130 YEARS as seasonal virus plummets by 95%

How Hospital Design Is Actually Making Us Sicker - Cheddar Explains

What are the most common misconceptions about furniture free? Well these are my top three!